The best argument against collectivist economic policies comes from examining the places that have tried to implement them — and then discarded them. In a short period of time following the collapse of the Soviet Union, for instance, Eastern Europeans went from having to wake up early to stand in long lines for their daily bread, to shopping in supermarkets stocked with an abundance of food from around the world. On a smaller scale, we can see the effects of miniature, Soviet-style welfare states on aboriginal reserves, right here in Canada.

It is unconscionable that, in this day and age, we would continue to maintain a colonial attitude that treats an entire group of Canadian citizens as wards of the state, but that is exactly how the Canadian government’s relationship with First Nations has been institutionalized. Enacted less than a decade after confederation, the Indian Act places strict limits on First Nations’ property rights. Under the terms of the act, the Crown maintains ownership over all reserve land, and grants Indians the right to utilize it. If any Indian wants to take “possession” of a piece of property, or the band wants to lease land to non-indians, the transaction must be approved by the central government in Ottawa.

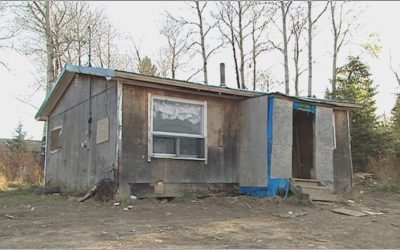

Canadians are all too often reminded of the devastating consequences this dependent relationship has produced, the latest of which is the thirdworld housing conditions on the Attawapiskat reserve in Northern Ontario. The lack of property rights on reserves means that bands have a hard time monetizing land. Existing structures become run down because people do not take pride of ownership in houses they do not own; and families are unable to use properties as collateral to take out loans, which would allow them to invest in businesses or real estate development.

The result is that communities are allowed to slowly degrade, and when the inevitable crisis becomes apparent, the band’s only option is to turn to the federal government for handouts. Allowing private property rights on reserves would certainly not solve all the problems faced by our First Nations communities, but it would go a long way toward allowing aboriginal people to deal more effectively with their own issues. We were therefore pleased to see the House of Commons Finance Committee recommend that the government “examine the concept of a First Nations Property Ownership Act as proposed by the First Nations Tax Commission,” in its pre-budget report. While there is no formal proposal for the act, it is certainly an idea whose time has come.

The concept underlying the act would allow First Nations to opt-into a system whereby legal title over lands would be held by reserves, instead of the federal government. Reserves would then have the ability to maintain community ownership over the lands, or transfer ownership to individuals.

Land titles would be dealt with in much the same way as they are off reserve. Just as the Crown maintains the right to set rules over zoning and building codes, as well as the power of taxation and expropriation, First Nations would be granted the same powers over their lands. This regime would allow individual bands to determine whether land could be sold, or leased, to its members, or even to non-aboriginals.

Such a move would significantly increase the value of First Nations’ land, because it could be bought and sold on the open market, giving First Nations the ability to attract more investment from off the reserve. It would allow residents to take out mortgages, invest private capital to upgrade their houses, plan for their retirement and pass property along to future generations.

This would be a stark contrast to the current situation, where people have no incentive to invest in, or maintain, existing dwellings, because they don’t have any skin in the game. Houses often become overcrowded and run down, and reserves are forced to wait for the federal government to fix the situation.

Private property rights are an essential element in a market economy, and they will be a cornerstone to the future success of our aboriginal peoples. Although similar ideas have met with stiff resistance in the past, we hope that giving First Nations more control over how their land is utilized, and allowing individual bands to opt out of the system, will make it palatable to all parties. We therefore encourage the government to adopt the recommendation of the House Finance Committee to work with the First Nations Tax Commission and other relevant stake holders to create the First Nations Property Ownership Act.