As of now, Indigenous communities have been spared from the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, although some health officials cautioned that the next two weeks will be important to see the extent of the outbreak in Indigenous communities.

Unless that state of affairs changes, Indigenous communities may provide some insights to mainstream communities in Canada on how to avoid the worst effects of these outbreaks.

As of April 30, Indigenous Services Canada reported there were 131 active cases of COVID-19 in a total of 23 Indigenous communities across Canada. Earlier in the month, officials said the cases were in Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Quebec. For perspective, First Nation leaders say there are 634 recognized First Nations in Canada. Thus far, the vast majority have not been affected by the pandemic. That may change, but let’s hope not.

According to CTV News, in one case in Alberta, the infections were traced to a nearby meatpacking plant. In one Saskatchewan case, two elders died in a care facility.

In a previous op-ed by the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, mentioned the significant risks that could come from outbreaks in First Nation communities, and those insights still hold, but there have been some unique circumstances that may have acted as a two-edged sword in protecting Indigenous communities from mass outbreaks.

The first is the isolation of many Indigenous communities, with some of these communities accessible by way of airplanes or winter roads. This isolation may have spared many of these communities from being exposed to people who were themselves exposed. By and large, the virus is hitting the larger urban centres hardest. The concern was that this isolation brings it a lack of access to proper medical resources to deal with a COVID-19 outbreak, but it seems isolation itself has shielded these communities. This only reinforces that these communities be closed off to visitors, and including, unfortunately, even returning band members to their own communities. It seems the early decision to close these communities to outsiders was the right one.

Members who have been off reserve or travelled overseas, of course, are at greatest risk of exposure. These members must be tested prior to relocating to their home reserves.

Also, on many reserves, housing is spaced apart, sometimes by a significant degree. The vast majority of First Nation communities are in rural or semi-rural areas, where there is significant space to keep away from others, thus making social distancing an easier thing to do. As stated before in the previous op-ed, crowded housing is a perfect recipe for spreading infectious diseases, such as was seen in the case of tuberculosis on many reserves, and would be with COVID-19 now. However, if people can keep away from others in general, there is much less risk of exposure at all.

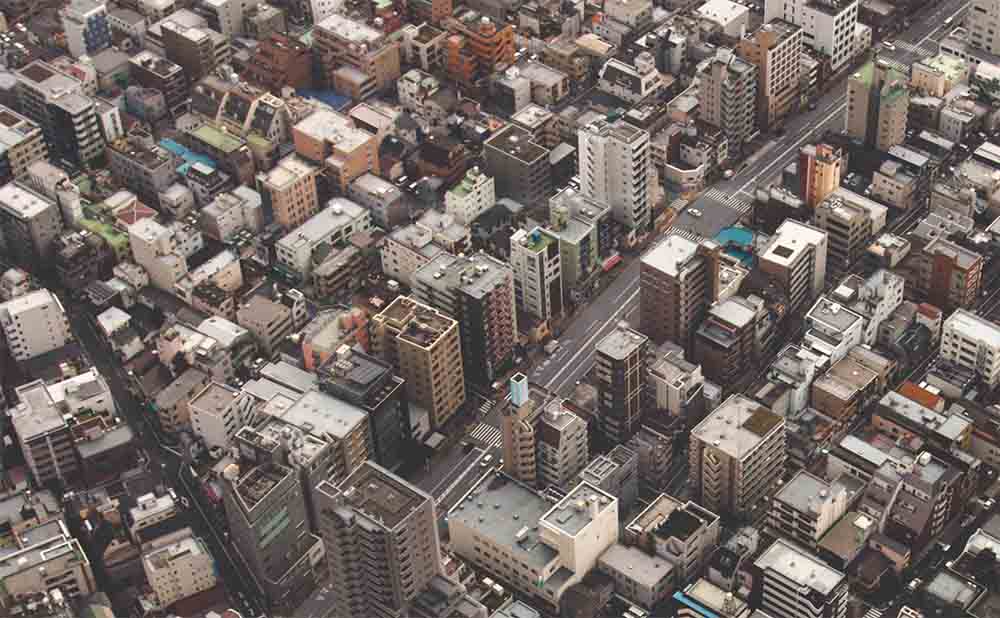

This past April, Philip Salzman, a senior research fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy published a commentary that focused on the issue of “dangerous density” in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak, and indeed all outbreaks. Looking at data from the United States, the author noted that states with heavily rural and low-density populations had the lowest number of COVID-19 infections, whereas states with large, dense urban regions were hit the hardest. This has largely been the case with Canada as well and other jurisdictions. Salzman, considering these findings, questioned whether this reality should make city planners rethink our city living.

Do isolated First Nations – minus the obvious problem of overcrowded and substandard housing – offer insight to mainstream Canada on how to better minimize the risks of spreading deadly infectious diseases like COVID-19?

Perhaps this apparent resilience of remote First Nations to these outbreaks due to their heavily rural location may give rise to changes in how we plan and manage our cities. Perhaps the orientation towards higher density, high rise urban centres may change.

So, we should continue to watch First Nations closely to see if the outbreak worsens. Thankfully, up until now, it seems these communities have been shielded somewhat from exposure. With the right policy decisions, this will likely remain the case.

Joseph Quesnel is a research associate with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. www.fcpp.org