For the 30 million Americans who depend on the Colorado River for their water, this past winter’s soaking rains and snows will only leave them thirsting for more.

In that Lake Mead, the West’s largest and most important reservoir, remains perilously near the level of 1,075 feet at which the U.S. Secretary of the Interior would likely declare a water shortage, for the first time in the nearly century-old history of the Colorado River system. Such a shortage would parch Nevada, Arizona and California with severe water-use restrictions. There alone, some 20 million people depend on Lake Mead’s supplies.

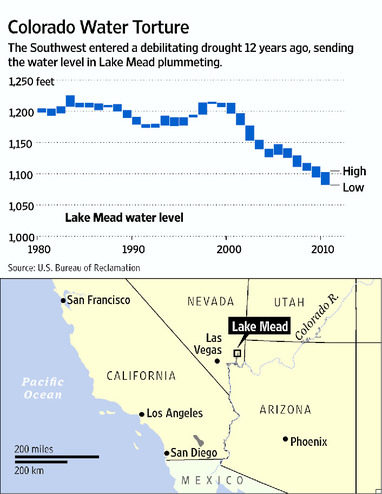

The fierce winter did bring some good news. The vast lake is rising for only the second time since the Southwest entered a debilitating drought 12 years ago. The water is 14 feet higher so far, and is projected to rise about nine feet more from the spring’s snowmelt by the end of the current water year in September. That takes into account the expected drawdown.

But even these fresh torrents are nowhere near enough to make up for the dozen-year deficit. The metropolitan areas that rely on Lake Mead, including Los Angeles, Las Vegas and Phoenix, remain at risk for shortages and severe water restrictions in the coming decades, as the Southwest—like many arid parts of the world—struggles to balance rapid growth with tight water supplies.

Lake Mead’s water level now stands at 1,096 feet, near its lowest point since the reservoir began filling in the 1930s and 110 feet below when the drought began in 1999, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The lake last rose in 2005.

Already, that low level has forced the bureau to cut power from the lake’s Hoover Dam by 20%. Recreational amenities including fishing and boating have been disrupted. Managers of the Las Vegas Boat Harbor say they have had to move their 630-slip marina at least once a year with the shrinking shoreline, at a cost of $100,000 per relocation.

"This [wet winter] buys us some time, but it doesn’t mean we’re out of the woods," Bruce Moore, a division manager at the Southern Nevada Water Authority, said recently as he surveyed the lake, where two fishing piers extend over now-dry Boulder Harbor.

The largest manmade reservoir in North America, Lake Mead serves as the principal storage facility for Colorado River water in California, Arizona and Nevada, the "lower basin" states. They share water from the 1,400-mile river with the "upper basin" states of Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico and Utah.

Under a 1922 pact, the two basins split 15 million acre-feet of water—the amount of water covering one acre a foot deep—from the river annually, with the more populated lower basin taking its full share while the less developed upper basin banks much of its half in Lake Powell on the Utah-Arizona border. Mexico is entitled to 1.5 million acre-feet annually. An acre-foot is roughly the amount of water used by a family of four in a year.

But the Colorado’s reliability has come into question in recent years amid drought and soaring demand. One issue: the 1922 accord was signed during one of the wettest years on record in the Southwest, setting apportionments that water managers say now appear too generous given the region’s frequency of drought.

Under the pact, the upper basin must deliver a minimum of 75 million acre-feet of water over a 10-year period to the lower basin, or an average of 7.5 million annually. If it fails, it can be ordered to do so by the courts. That, say upper-basin water managers, puts the 10 million people in their states at risk of shortages.

"If there was a call for us to curtail [water usage], those shortages could be significant," said Jim Lochhead, chief executive officer of Denver Water, which relies on the Colorado for half its water supply to about 1.2 million people in metropolitan Denver.

Lower-basin states are vulnerable, too. If Lake Mead sinks to 1,075 feet and a shortage is declared, Arizona would lose 320,000 acre-feet, or about 12% of its share, said Terry Fulp, a deputy regional director of the Bureau of Reclamation office in Boulder City. Nevada would lose about 13,000 acre-feet, or 4% its allotment. Politically powerful California, which is entitled to 4.4 million acre-feet, wouldn’t be immediately affected, under agreements over which water agency has greater rights to the river.

The Southern California district, which gets half its imported water from the Colorado, has since made up the shortfall through conservation and efficiency measures, but Mr. Kightlinger said the outlook is worrisome.

Water agencies are scrambling to avert a hot dry disaster. The Central Arizona Project has stockpiled four million acre-feet of its Colorado River water in underground aquifers, said David Modeer, general manager of the water agency in Phoenix. The Southern Nevada Water Authority in 2009 began a $780 million project to build a third intake facility from Lake Mead as part of a plan to keep siphoning water to Las Vegas if the two existing intakes, which are at a higher level, end up too low to pump declining water levels. That project, which entails digging a tunnel three miles under the lake, is set to be completed in 2014.

Patricia Mulroy, general manager of the Nevada agency, said the state also is working with other states and the federal government to try to maintain the lake’s level. For example, the U.S. and Mexico last year signed an agreement to keep 260,000 acre-feet of Mexico’s share of river water in Lake Mead through 2013, after a 2010 earthquake in Baja California damaged water infrastructure there. That will add up to four feet of water in the lake, officials estimate, though Mexico will keep its claim to the water.

State and federal agencies are also working on ways to reclaim more water, such as desalination of irrigation runoff. "There will be no silver bullet," Ms. Mulroy said. "There will be a mosaic of options."

But Arizona’s and Nevada’s losses would grow as water levels drop, with curtailments eventually hitting California. Already, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which serves 19 million people, has lost nearly half a million acre-feet, or half of what it imports annually from the Colorado. Federal officials ordered the agency in 2003 to stop using water from the river that had been designated as a surplus prior to the drought, said Jeff Kightlinger, general manager of the district.

But Arizona’s and Nevada’s losses would grow as water levels drop, with curtailments eventually hitting California. Already, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which serves 19 million people, has lost nearly half a million acre-feet, or half of what it imports annually from the Colorado. Federal officials ordered the agency in 2003 to stop using water from the river that had been designated as a surplus prior to the drought, said Jeff Kightlinger, general manager of the district.