The federal election has highlighted the need for transportation infrastructure in Canada’s Far North with the recent federal budget’s announcement of $150-million for an Arctic highway between Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk. While the goal of a national highway system from sea to sea to sea can be seen as an important nation-building goal, the fact remains that the east-west Trans-Canada Highway system is still inadequate despite its crucial role as a national transportation artery. While much of Highway 1, as it is known in much of Canada, is four lanes, it is still deficient in parts of Eastern and Western Canada. Moreover, even what is four lanes is still a far cry from a worldclass highway system, as exists in the U.S. Interstate system or the European autobahns.

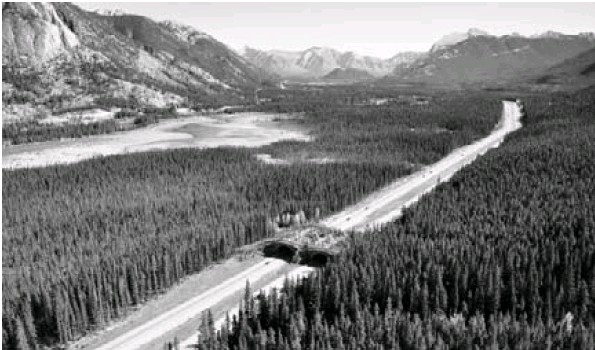

Not all of the Trans-Canada looks like this stretch near Banff, Alta.

Canada is the largest developed country in the world without a system of fully grade-separated roadways that allow uninterrupted traffic flow between its major urban centres. The key roadblocks include the two-lane stretches from the Manitoba border to Sudbury and much of the route between the Alberta border and Kamloops. Most importantly, the Trans-Canada is still a two-lane stretch through the vital zone of transit through northwestern Ontario connecting the East with the West from the Manitoba border to Sudbury, leaving the nation’s east-west flow of personal and commercial traffic subject to the whims of an errant moose. The slow travel times and disruptions make cutting through the United States an attractive option for east-west travellers, despite the absence of an Interstate route along the border, but U.S. bordercrossing formalities have also made this more difficult and time-consuming.

Canada pays a price for this substandard system in the form of higher transportation costs due to longer travel times, increased traffic deaths, reduced tourism opportunities and a diminished sense of national security, given the reduced possibility of rapidly moving assistance from one part of the country to another in times of national distress. The safety aspect alone is important, as it has been estimated that in its first 40 years, the U.S. Interstate Highway System reduced traffic fatalities by 187,000 deaths. Are American lives worth so much more than our own that we cannot invest in the safety of our roadways? Moreover, careful analyses have found that U.S. Interstate highway investments have consistently reduced production and distribution costs and raised productivity across the industrial spectrum, yielding large returns to society.

In a recent policy paper for the Frontier Center for Public Policy, Wendell Cox makes the case for a Canadian autobahn system that would upgrade the entire transcontinental route from Halifax through Toronto to Vancouver to motorway standard at a cost of about $28-billion. This constitutes a hefty investment that would have to compete for scarce public funds. At present, however, there is no such competition for funds because there appears to be no recognition in Ottawa of the potential value of the national highway project.

While road transportation is a provincial responsibility, establishing and maintaining a national system of highways definitely has an important nation-building federal role. Yet the national highway system has no prominence on the Infrastructure Canada website and there is no discussion of its potential merits and costs between or during elections. What was the contribution of the soon-to-be-completed Canada Action Plan to improvement of the national highway system? Were strategic components of national highway expansion even considered?

Despite the substantial price tag, development of a true national highway represents a very small fraction of our current GDP and the economic impacts of the project would be substantial both in the short and long runs. Although some might argue that the time for investment in highways has passed because of environmental concerns, we see little indication that motor vehicle transportation is losing steam as cars and trucks become more fuel efficient and environmentally friendly. As for financing, we already collect substantial gasoline taxes in this country and dedicating a portion of those to upgrading the highway system rather than general revenues makes more sense.