The Alberta Premier recently raised the possibility of implementing a provincial police service.

“We will invite the panel to explore the feasibility of establishing an Alberta provincial police force by ending the Alberta Police Service Agreement with the Government of Canada,” 1

The Premier’s statement, however, was followed by an announcement by Justice Minister Doug Schweitzer that Alberta was set to contract an additional 300 uniformed RCMP officers to join detachments and specialized RCMP units across the province, increasing the current complement of RCMP officers from 1,600 to 1,900. According to the Alberta Justice Minister:

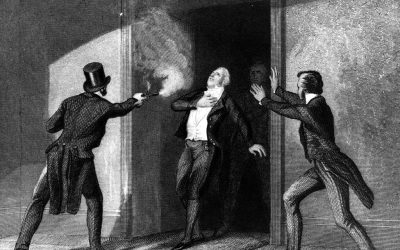

“This is the largest single investment in rural policing since the March West,” when hundreds of North-West Mounted Police officers traveled across the Prairies in 1874, Schweitzer told CBC News on Monday.2

These conflicting statements may be a signal of an internal debate about where Alberta wants to go with its policing obligations. While the Premier’s statement may have been part of a larger strategy to signal Alberta’s desire to gain greater autonomy from Ottawa, it raises important considerations.

Understanding the role of policing in Canadian society, particularly Western Canada requires a brief structural and historical context.

Structurally, policing in Canada is administered on three levels: municipal, provincial, and federal. There are 141 stand-alone municipal police services and thirty-six First Nations self-administered services across Canada. 3

There are also three provincial police services: the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary (RNC), the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), and Sûreté du Québec (SQ).

The RCMP is responsible for all federal policing matters including contract policing to provinces without their own provincial services – including Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.

Notwithstanding contract policing, all police services operate under the direction of the Minister of Justice and Solicitor General within the contracting province. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the provinces to ensure that adequate and effective policing is maintained throughout their jurisdiction.4

Within provinces with provincial police services, smaller municipalities may contract with the provincial police for their policing services, governed by a municipal police services boards, or as is to be the case in Alberta, contribute to subsidizing local policing.

Self-administered First Nations police services are created under agreements between the federal, provincial, and territorial governments under a cost-sharing agreement between the federal government (52%) and provincial/territorial governments (48%). The communities are responsible for governing the police service through a police board, band council, or other authority.5

The structure of policing has changed over time and all provinces have not always had provincial police services or always contracted to the RCMP.

Historically, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba had been under the stewardship of the Royal North-West Mounted Police (RNWMP) into the late 1800’s.

By 1916-17, conflicting interests over enforcement of provincial anti-liquor laws and the wartime national security priorities of the federal government, particularly in Western Canada, resulted in the replacement of the RNWMP with the Alberta Provincial Police (APP) and the Saskatchewan Provincial Police (SPP).6

However, during the Great Depression, Saskatchewan’s concerns about the cost of three tiers of policing (municipal, provincial and federal) led it to return to contracting with the RCMP in 1928– known as the “subsidy model”. Alberta and Manitoba followed Saskatchewan’s decision, returning to contract policing in 1932.

The British Columbia Provincial Police (BCPP), created in 1858, remained in place until 1950 when B.C. also contracted its provincial policing to the RCMP. Similar agreements followed in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

The policing of First Nations communities on the other hand have evolved collaterally on an ad hoc basis. Policed by the RCMP, in many instances, the federal government used the RCMP to enforce social policies, such as the placement of Aboriginal youth in residential schools; policies that have resulted in a loss of trust and ongoing antagonism between First Nations peoples and the RCMP.7

Between 1967 and 1990 a total of twenty-five federal and provincial reports were published that addressed the involvement of Aboriginal persons with criminal justice systems. Twenty-two of these commissions or investigations offered recommendations that were summarized by the Alberta Government, including the importance of expanding policing services to First Nations.8 These reports have been reflective of Alberta’s ongoing efforts to address criminal justice issues involving First Nations peoples.

Premier Kenny’s vision to bring back the Alberta Provincial Police has historical precedence, and is perhaps also necessary, for economic and socio-cultural reasons.

Policing is far more than just about crime control. From a socio-cultural perspective, police services are guardians of the communities they protect, but they are also symbols of the values of the societies they represent. Citizens are also likely to relate to “their” police as symbols by which a grander, cohesive national past can be recalled or a troubled, fractured present explained.9

Studies confirm that citizens think about their police in ways less to do with the risk of victimization (instrumental concerns about personal safety), and more to do with judgments of social cohesion and moral consensus (expressive concerns about neighbourhood stability, cohesion, and loss of collective authority).10

How police organizations are structured, governed, and how they uphold the rights of citizens and stakeholders serve as key elements in earning public trust and contributing to the development of social cohesion and community.11 The police are, therefore, themselves a component of social cohesion, as well as the providers and maintainers of it; and if this is the case, then Albertans should consider carefully the nature and context of policing policy within the larger framework of social cohesion and evolving community partnerships.

If history is to provide a lesson for policing, it is that change is inevitable and that policing is replete with competing and often conflicting interests. As earlier consolidations and separations of policing jurisdictions were based on competing and conflicting national and regional interests, Canada today faces similar, and perhaps more intensely competing interests.

The RCMP is faced with an increasingly complex national and international policing landscape, which in many instances must take priority over provincial, municipal and community policing. The RCMP operates across Canada with a wide set of responsibilities that impact the Service as a whole – it cannot fully divest of its national and international demands for resources, even where contracted to provide provincial policing. In the least, officers at all levels will be motivated by national opportunities for advancement and special assignments; motivational incentives that will conflict and can detract from provincial priorities. The RCMP will, therefore, continue to have conflicting interests between their national and contract obligations. As Michael Kempa, University of Ottawa criminology professor notes:

“There’s been a raging debate around the RCMP for more than two decades as to whether or not they can continue to focus on federal policing issues alongside contracted provincial and sometimes municipal policing issues as well”. 12

Furthermore, Alberta has a significant First Nations population, which will continue to exert increasing influence in provincial affairs. It is also a community that harbours deep scars attributed to misguided federal policies enforced by the RCMP; scars that have resulted in lasting mistrust and antagonism between First Nations and non-First Nations communities. First Nations continue to experience higher rates of crime and over-representation in the justice systems; a state of affairs that extracts a heavy cost on Alberta’s economy.13

Despite policing Albertans since 1932, the RCMP has not lived up to the standards that Albertans should expect. The RCMP’s failure reflected in the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) inquiry is an embarrassing and costly example of this failure. A failure reflected in the apology by Brenda Lucki, the RCMP Commissioner:

“On behalf of myself and my organization, I am truly sorry for the loss of your loved ones and for the pain this has caused you, your families, and your communities. I’m sorry that for too many of you, the RCMP was not the police service you needed it to be during this terrible time in your life.”14

Anthony Merchant, a lawyer representing plaintiffs in a proposed $600-million class action against the RCMP over the handling of MMIWG investigations notes: “there exists a systemic disregard and antipathy”.15

Furthermore, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba all report notably higher crime severity indices and crime rate in comparison to their counterparts, with the exception of Yukon, North West Territories, and Nunavut, which are also policed by the RCMP.16

As the Alberta Justice Minister himself acknowledges:

“(People) simply don’t feel safe right now in their communities,” and that “This is having an incredible toll on so many people across rural Alberta.”

The RCMP has serious problems and challenges of public trust. According to a report by Global News, more than $220 million has been spent in the last twenty years on everything from sexual harassment lawsuits to human rights complaints and federal inquiries into nepotism, workplace bullying and turf wars with other police agencies. A figure that, amongst other misconduct, includes funds spent paying out lawsuits related to employee claims as well as external claims including use of force, malicious prosecution and failing to protect informants.17

Moreover, Alberta’s Police Act diminishes the RCMP’s accountability to Albertans; an important concession reflected in Section 49 of the Act:

“Notwithstanding sections 43 to 48 and subject to any agreement entered into between the Government of Canada and the Government of Alberta or a municipality, as the case may be, any complaints in Alberta with respect to members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police shall be resolved in accordance with the laws governing complaints and discipline within the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.”18

The citizens of Alberta have been impacted by elevated crime for far too long, and need to feel safer, to have a better quality of life, and to have confidence in their police. Alberta owes its citizens policing that is committed to their communities – community policing cannot be delivered by importing more RCMP officers. Alberta’s policing has not kept up with the needs of Albertans and Alberta’s own distinct ethnographic needs, social, and economic requirements.

Although the minister has promised to increase the number of RCMP officers from 1,600 to 1,900 at a cost of $286 million over the next five years, this alone is unlikely to improve perceived and real concerns for public safety, particularly in rural Alberta.19

Nonetheless, Alberta is enacting legislation requiring communities with fewer than 5,000 people to pick up more of the policing tab. The current Provincial Police Service Agreement splits the $374.8-million annual cost of rural RCMP between the provincial government (seventy percent) and the federal government (thirty percent). Beginning in 2020, counties, municipal districts and small towns will begin paying ten percent of those costs. Their share will rise every year to reach thirty percent of policing costs by 2023.20

Over the next five years, small municipalities are expected to contribute $200 million for policing while the federal government will chip in nearly $86 million.21 By some estimates it will increase Albertans’ taxes by $400.22

These announcements promise more RCMP contract officers, more taxes, and no guarantee that anything will change the experience of the past eighty-eight years of RCMP policing in Alberta.

Alberta deserves policing by officers who have deep ties, obligations, and loyalty to their communities. Albertans should be concerned that contract officers assigned to Alberta are not necessarily from Alberta, with roots and ties to Alberta. Furthermore, Alberta should be creating jobs for Albertans, and for their families, who are likely to live and retire within the province. Contract policing essentially transfers Albertan’s tax contributions, and potential reinvestments, to Ottawa.

This may be the largest single investment in rural policing since the March West by the North-West Mounted Police across the Prairies in 1874, but that expansion was about keeping the country together, not building communities. Any idea of combining federal policing and community based policing is a contradiction of terms that has been tried and failed.

The only federalist separation between Upper and Lower Canada seems to be between the provinces that have a provincial police service and those which continue to be policed federally.

The RCMP is a proud and iconic symbol of Canada, made up of proud hard-working members from across Canada, however, it is time for Alberta to consider taking back it’s policing, to create local ownership, accountability, and to hire Albertans to police Alberta. Premier Jason Kenney’s vision is based on precedence, and is timely. Albertans should determine their own policing priorities based on their particular needs. It may be time to bring back the Alberta Provincial Police.

[show_more more=”SeeEndnotes” less=”Close Endnotes”]

Endnotes

1. CBC, Why Alberta is considering severing ties with the RCMP; https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/alberta-police-force-rcmp-kenney-fair-deal-1.5354946

2. CBC, Municipalities will pay up as Alberta adds 300 RCMP officers to combat rural crime; https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/alberta-rcmp-rural-crime-schweitzer-1.5383062

3. Police resources in Canada, 2017; Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics; https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2018001/article/54912-eng.pdf

4. Revised Statutes of Alberta; http://www.qp.alberta.ca/1266.cfm?page=P17.cfm&leg_type=Acts&isbncln=9780779814732

5. Police resources in Canada, 2017; Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics; https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2018001/article/54912-eng.pdf

6. Galloping off in all directions: An analysis of the new federal– provincial agreement for RCMP contract police services and some implications for the future of Canadian policing Canadian Public Administration volume 55, no. 3 (September 2012), pp. 433–450 © The Institute of Public Administration of Canada 2012

7. Global News, The RCMP was created to control Indigenous people. Can that relationship be reset?; https://power97.com/news/5381480/rcmp-indigenous-relationship/

8. University of Regina; First Nations Policing: A Review of the Literature; https://www.justiceandsafety.ca/rsu_docs/aboriginal-policing—complete-with-cover.pdf

9. Jonathan Jackson et al., “Why Do People Comply with the Law? Legitimacy and the Influence of Legal Institutions,” British Journal of Criminology (2012).

10. Jonathan Jackson et al., “Why Do People Comply with the Law? Legitimacy and the Influence of Legal Institutions,” British Journal of Criminology (2012).

11. Anil Anand; Mending Broken Fences Policing

12. CBC, Why Alberta is considering severing ties with the RCMP; https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/alberta-police-force-rcmp-kenney-fair-deal-1.5354946

13. Aboriginal Policing in Rural Canada: Establishing a Research Agenda; International Journal of Rural Criminology, Volume 2, Issue 1 (December), 2013

14. Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Statement of apology to families of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls; http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/news/2018/statement-apology-families-missing-and-murdered-indigenous-women-and-girls

15. Global News, The RCMP was created to control Indigenous people. Can that relationship be reset?; https://power97.com/news/5381480/rcmp-indigenous-relationship/

16. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Police Resources in Canada 2017; https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190722/dq190722a-eng.pdf

17. Global News, $220M and counting: The cost of the RCMP’s ‘culture of dysfunction’; https://globalnews.ca/news/4864037/rcmp-culture-of-dysfunction/

18. Province of Alberta Police Act, Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000; http://www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/P17.pdf

19. Lethbridge News Now, Province announces $286-million to bolster rural policing; https://lethbridgenewsnow.com/2019/12/04/province-announces-286-million-to-bolster-rural-policing/

20. Edmonton Journal, Province to add 300 rural RCMP officers with municipalities sharing the bill; https://edmontonjournal.com/news/politics/province-to-add-300-rural-rcmp-officers-with-municipalities-sharing-the-bill

21. Edmonton Journal, Province to add 300 rural RCMP officers with municipalities sharing the bill; https://edmontonjournal.com/news/politics/province-to-add-300-rural-rcmp-officers-with-municipalities-sharing-the-bill

22. CTV News, Municipalities to help pay for new rural policing model as Alberta adds hundreds of Mounties; https://edmonton.ctvnews.ca/municipalities-to-help-pay-for-new-rural-policing-model-as-alberta-adds-hundreds-of-mounties-1.4712835

[/show_more]

Anil Anand is a Research Associate with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. Anil served as a police officer for 29 years; during his career some of his assignments included divisional officer, undercover narcotics officer, and intelligence officer. He has worked in Professional Standards, Business Intelligence, Corporate Communications, the Ipperwash Inquiry (judicial public inquiry), and Interpol.