Good news has many fathers, the saying goes, while bad news is an orphan. So it was when the Covid-19 case numbers and casualty counts began to recede late last spring. Even faster than dandelions sprouting, variations on “We have flattened the curve” became among the most widespread utterances by political leaders and public health officials.

“Saskatchewan has reduced the spread of Covid-19. We have flattened the curve,” exclaimed Premier Scott Moe at the end of April. Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer, Theresa Tam, said the same in early May: “We have collectively brought down the rate of infection. We are flattening the curve.” Jennifer Russell, Chief Medical Officer of New Brunswick, concurred. “Going as long as we have with no new cases is a significant achievement,” she said. “We have flattened the curve in New Brunswick.” As did Deena Hinshaw, Alberta’s Chief Medical Officer of Health. “We have, I think, flattened the curve in general across the province,” she said on May 6.

You get the idea. Curve = Flattened. Reason = Us.

Did Covid-19 really recede because “we” (that is to say, our betters, the experts and politicians) “flattened” the curve like so much road-kill pulverized beneath the wheels of a monster truck? At the time, contrarian views on the coronavirus were muted and scattered. The apparent consensus view of public health officials, politicians and most media went almost unchallenged. Acknowledgement, if there was any, that new viral epidemics tend not to be neatly controllable was overshadowed by the orgy of self-congratulation.

And for a while last summer, it appeared as if our governing class had pulled off one of the most successful political shell games ever seen. A foreign virus appeared. It was met on the epidemiological battlefield and, after a few nervous moments and a regrettable death toll, it lay vanquished. Slain by sheer political determination and commitment. Having issued wildly inflated predictions of case-counts and fatalities based on modelling that was soon proven egregiously incorrect (but never officially repudiated), and then vowing to “flatten the curve” through unprecedented and, it turned out, catastrophically damaging measures, there was a clear temptation for political leaders and “top doctors” to praise themselves and each other for the collapse in Covid-19 cases and fatalities.In Quebec, for example, it was popular to talk of “slapping down the curve,” a process that eventually led Premier François Legault to exult over his province’s “extraordinary” success in halting the virus last April. In B.C., they talked about “bending” the curve. The bombast and boasting proved contagious, with unions and business leaders soon also crowing about their contributions to curve flattening.

By then, the relatively few who had cared to look realized this was an eminently contestable claim. Leaders in a number of countries and a few U.S. states had refused to go along with lockdown mania. And while the particular results in those jurisdictions varied widely, as they did in lockdown jurisdictions, virtually every place that had been hit with a first wave over the winter experienced a sharp or precipitous decline by late spring – whether it locked down or not.

Of course, this is not to say that sound and long-understood practices such as hand-washing, disinfecting, distancing, testing and prompt isolation of the infectious weren’t important; as in any infectious disease epidemic, they were and still are. As are intensive research into treatments and vaccines. But the broader point left unlearned was that the impact of human intervention on this pandemic was unknowable and, therefore, the associated claims were dubious.

To believe – or to claim – that correlation implies causation is one of the most basic and longest-known of logical fallacies. There’s a whole body of literature on it. But that did not seem to bother Canada’s expert and leadership elites – or those in many other countries. Claiming credit for something they barely understood and did not actually control was wildly risky. Had the preceding weeks of panic clouded their judgment? What if Covid-19 didn’t stay gone? They could be walking into a political trap – one of their own creation.

It has been known since the 1840s (a more technical analysis is here) that epidemics follow a natural trajectory: they appear, they rise ominously and in apparent open-ended fashion, they peak or plateau, and they fall again. As for respiratory viruses, they tend to appear in autumn and winter months when people are tightly packed indoors, and recede upon the arrival of warmer weather, when people generally spend more time outdoors, exercising and gaining vitamin D from the sun. Why anyone expected Covid-19 to behave differently remains a mystery. Evidence quickly emerged that this virus thrives in cooler environments, is vulnerable to heat and dies under ultraviolet radiation. Months later, even Anthony Fauci admitted that sunlight kills this virus.

And so the political shell game worked for a while. Canada’s premiers spent the late spring, summer and early fall watching their approval rates soar in the vaporous trails of their own mythmaking. This was goosed by a torrent of feel-good announcements standing in for concrete economic recovery. During this period Canada spent more than any country in the world on income replacement. Canadian average income actually rose amidst the pandemic.

After this relatively pleasant summer, marked by widespread if disjointed and partial reopening of various sectors, activities and livelihoods, something “odd” occurred. Covid-19 came roaring back. Given the success of all that curve-flattening just a few months prior, how could such a thing happen? What should always have been regarded as an essentially uncontrollable but temporary natural phenomenon had been redefined as something that could be managed to the ground and out of existence. If it reappeared, then some kind of failure must have occurred. And somebody had to be at fault.

Faced with potential repudiation of their mighty accomplishments, a good number of politicians and top doctors – and much of the news media – began to blame the people themselves. Ontario Premier Doug Ford singled out those moving around the province. “Despite the restrictions, we’ve seen growing numbers of people travelling between regions,” he groused. Alberta’s Hinshaw declared herself “disappointed” at the response from individuals and businesses trying to maintain a semblance of normalcy as restrictions increased in November. “I have asked for kindness, but also for firmness,” she said, somewhat ominously.

There has been a much larger and more insidious process of scapegoating running through the government response to Covid-19. Officials have tried to convince us that activities considered normal, necessary, healthy and wholesome since the dawn of time are instead dangerous, reckless and immoral. Plus, they implicitly redefined the process of getting sick itself into a transgression if not an actual crime. Like the basic trajectory of epidemics, recurring waves are a common feature recognized for over a century – such as during the Spanish flu. But now, the people were held at fault for Covid-19’s second wave.Globe and Mail columnist Gary Mason cast aside ambiguity, blaming the rise in Covid-19 figures on the “pure unadulterated selfishness” of folks failing to abide by every last public health recommendation. He later wrote, however, that it was “scapegoating” and racist to make comments about any identifiable groups that seemed to display disproportionately high rates of infection.

Quite a number of Canada’s earnest and well-meaning citizens seemed to swallow this outrageous sophistry. For a similarly large number, though, being held at fault was too much to take, for they were following all the rules. Not that most of these believed a second wave was natural, expectable and would need to run its course (mitigated of course by accepted palliative practices). They too considered it a manageable problem. But as they saw it, it was the politicians who were doing the mismanaging.

Given that these two groups together represent the large majority of Canadians, the second wave quickly morphed into a grave political threat. If leaders had only been honest with the public from the start – or at least a good bit humbler about their influence upon the pandemic’s trajectory – they might have avoided this conundrum. But it was not to be. The Covid-19 political trap was sprung.

Across the spectrum of public policy, political leaders have a great deal invested in the rightness of their point of view. Regardless of personal influence or involvement, they’re always keen to take credit for a booming economy, for example, and quick to cast the blame elsewhere when unemployment rises or growth slows. In truth, a great deal of economic success or failure, particularly in an open economy like Canada’s, is far beyond domestic control.

But anyone who claims credit for the good times must expect to face the music for the bad news. So it proved with Covid-19. Since our leadership class had claimed to have overcome it before – and had convinced most of the public that lockdowns and other government-imposed restrictions could “keep them safe” – they were now on the hook to do it all over again.

As the number of Covid-19 “cases” (that is, positive test results) began to rise in fall, then kept on rising, provincial leaders once again panicked. They realized they had to be seen to be acting decisively – even if what they did was of dubious benefit and imposed enormous collateral damage. Some premiers initially tried to keep businesses open and avoid the more strident demands for another lockdown. Alberta’s Jason Kenney and Saskatchewan’s Moe were two.

But even they were ground down by relentless pressure from the federal government, virulent and venomous rhetoric from political opponents – Kenney being accused of “negligence” and of having “enabled” the second wave by Alberta’s NDP leader, and of far worse on social media – fear-mongering by news media and self-interested organizations such as teachers’ unions, pompous pronouncements by various media-hungry experts and scientists, and enormous expectations from many everyday citizens conditioned to believe in the efficacy of ever-stricter measures.

The Prime Minister played a role in this process by implicitly threatening to deny the premiers federal funding if they did not fall into line by shuttering businesses and imposing restrictive legislation. This was after the World Health Organization, reversing its earlier stance, advised against imposing further lockdowns for anything but very short periods. The provinces fell in line one-by-one, imposing everything from bans on even tiny social gatherings to stay-at-home orders to outright curfews, crushing thousands more businesses, stripping Canada’s citizens of virtually all their civil rights, and vilifying dissenters.

The belief – or conceit – was that repeating the heretofore unprecedented measure of mass-quarantining a healthy population could wrestle down the virus. After all, it worked before! “Don’t let your guard down,” warned Toronto’s medical officer of health Eileen de Villa. In B.C. the province’s top doctor, Bonnie Henry, cast back to the alleged success of the previous lockdown to lay the foundation for the next. “We know what we need to do to turn this around and bend our curve back down,” she said. “Let’s flatten our curve once again.”

Instead of learning from their mistakes, our political leaders and “top doctors” just can’t seem to help themselves. In Alberta, for example, the case-count has been falling hard. “Our province has made remarkable progress over these past two months,” Hinshaw said on February 3. “We have bent the curve and every Albertan can be proud of that.” To her credit, she was sharing the “credit” for this fortunate result. Still, she was also reinforcing the narrative that human intervention itself steers the virus’s trajectory.

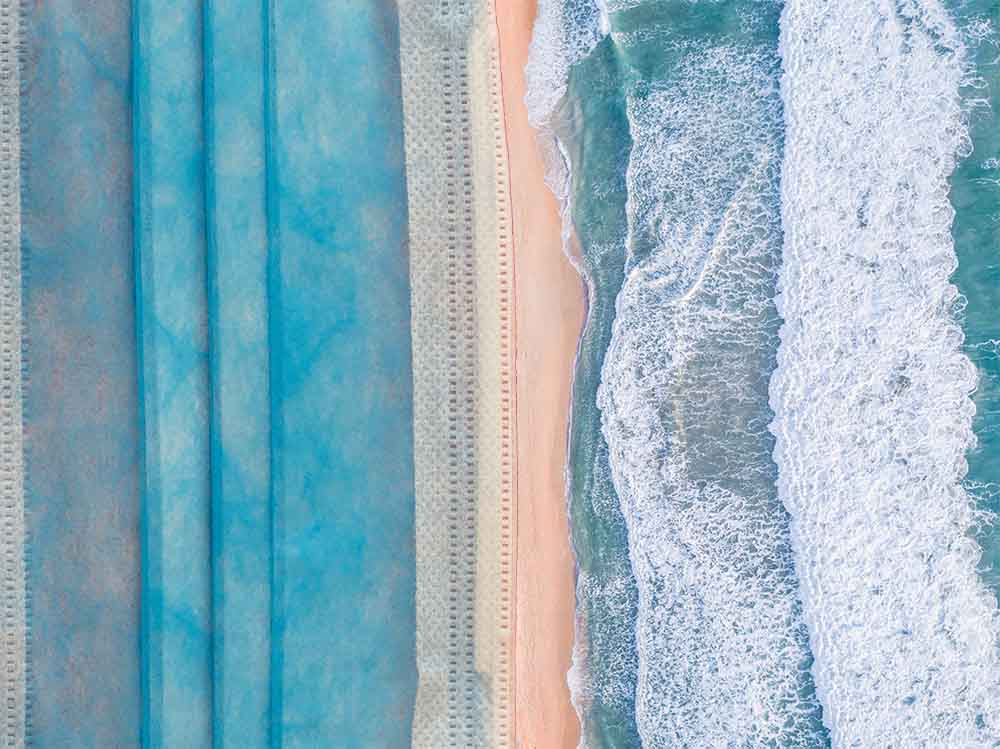

Such a stance is curious and troubling, for the clearest and most elementary metrics – the daily case count and the seven-day moving average – each had peaked and begun to decline before Alberta’s most severe lockdown measures took effect on December 13, as the accompanying graph shows. (Both numbers continued to decline immediately thereafter, before the new measures could have slowed the spread of the virus, with its purported 14-day incubation period.)

In this instance, the two phenomena of viral trajectory and government restrictions weren’t even correlated. The desired effect had commenced before the claimed cause had been implemented. But something that happens today – a new lockdown, for example – simply cannot be the cause of something else that has already occurred. Not even the very topmost of our top doctors, nor the wisest of our political leaders, are that good.

The continuing battle between those who believe massive government intervention remains key to defeating the virus and those who are appalled at the catastrophic damage this is wreaking will not go away even once the second wave recedes. The controversy will rage unless and until a consensus is reforged – at least within individual jurisdictions – about the appropriate management approach to this and similar future emergencies. The habit of our elites to claim credit where none is due and assign blame to the innocent can only obscure the issues and undermine any such fruitful process.

Re-published from www.c2cjournal.ca

Brian Giesbrecht is a retired Manitoba provincial court judge, Senior Fellow with the Frontier Center for Public Policy and frequent commentator on public policy issues. George Koch is Editor-in-Chief of C2C Journal.