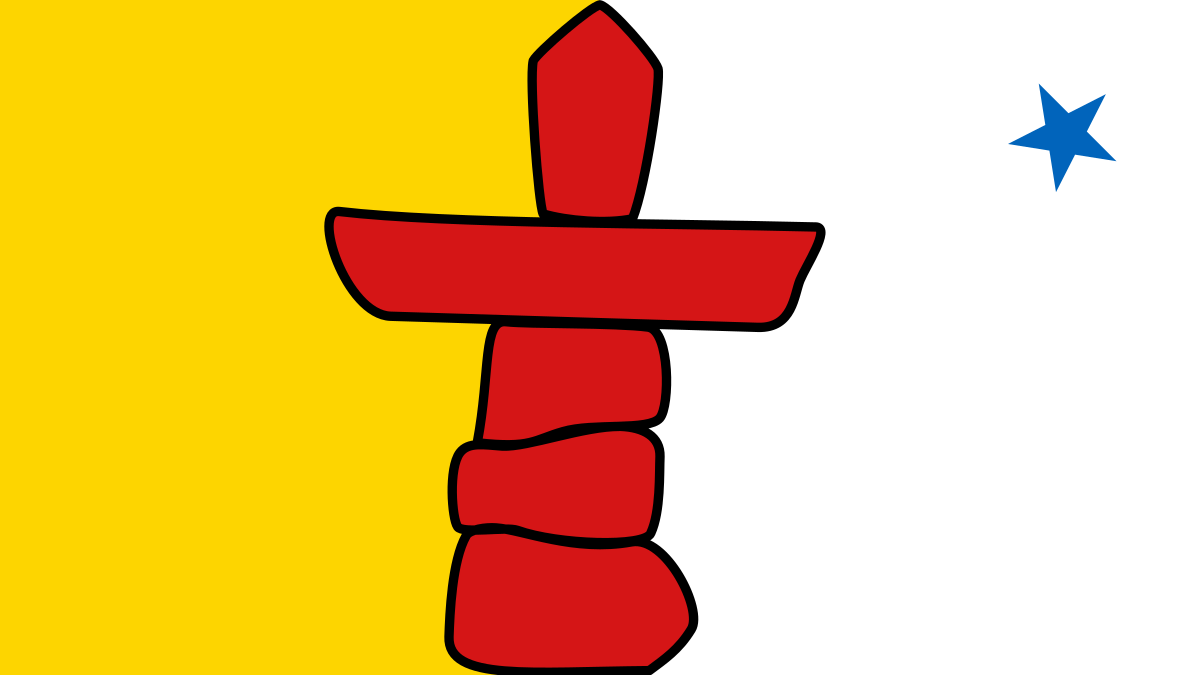

On January 18th the Nunavut territory in Canada’s eastern arctic, “Our Land” in Inuktitut, took control of natural resources, including mining and petroleum. Devolution follows the 1993 legislation to sever Nunavut from the Northwest Territories, implemented in 1999.

Responsibility for permitting and oversight of natural resource operations rests with the Nunavut Impact Review Board (NIRB). Can they do that job? Chairman Marjorie Kaviq has a BA science degree (Environmental and Resources) from Trent University, and she’s currently enrolled there for a Masters Degree in Educational Studies. She has no work industry experience. The other eight board members have no qualifications whatever.

Shackling natural resource development has become part of the Indigenous pathology on principle. The federal government had to overrule the NIRB’s recommendation to prevent expansion of the huge Baffinland iron mine so as to avert its threatened closure. The NIRB has also objected constantly to Agnico-Eagle’s gold mining operations. Despite the companies’ providing considerable training and high pay, Inuit fill only some 15 percent of the jobs in mining. Many want those jobs. But it’s now a high-tech industry and few Inuit have advanced skills.

The world needs arctic resources. But there’s a similar template in Greenland, sustained by Denmark’s taxpayers, for opposing development. A movement there wants to stop a huge mine in the south of the island that would deliver neodymium, used for wind turbines and combat aircraft, and also uranium.

There were high hopes on April 1, 1999 when Governor General Adrienne Clarkson performed the inauguration ceremony for Nunavut. Self-government was supposed to be more responsive to needs manifested by her being presented with a petition from an unemployed and homeless Inuk. With the fur trade defunct, Nunavut was supposed to deliver jobs and self-reliance.

Nunavut has lived up to expectations only for the elite. They hold highly paid but mostly figurehead positions. Outsiders do the professional work and also most low-skill work—like janitorial work at the hospital or driving taxi. Some Inuit also do intermediate-skilled jobs like operating heavy equipment. Many live on welfare, having been indoctrinated to believe in their entitlements, and with many being multi-generational recipients.

Largely duplicating the territorial government’s desk jobs, Inuit also do make-work at the land claims organization NTI (the land claims trust). It holds investments that may be worth billions, or perhaps $100,000 per Inuk in Nunavut. We don’t know how much is there or what they do because their website’s most recently posted annual statement is for 2018! It’s unlikely the fund’s value is keeping pace with increasing population and the rising cost of housing. Apart from meeting NTI’s payroll, some $10 million plus goes each year to investment advisors in southern Canada—none of them Inuit. The board refuses to buy desperately needed housing. That, they say, is the federal government’s responsibility. Yet the fund’s value may equal the annual subvention of Nunavut’s government by taxpayers. Inuit could solve many problems if they demanded its division into individual family trusts.

Nunavut’s leaders are prospering but many marginalized followers live in abject poverty and destitution. The question remains unaddressed as to whether next generations should be educated and trained for the high-tech economy or for some kind of presumably modified traditional lifestyle. The elite glorify the iconography of a lost Garden of Eden. But what do youth say they want? They see the stereotypical but no-longer-real life on the land as representing second-class citizenship. Most want the rewards and respect associated with skilled employment, although few are motivated to make that happen.

In the 1960s, Peter Pitseolak wrote in his memoirs, in Inuktitut, that he expected one or more of his grandchildren would become full-fledged medical doctors. Despite the needs, Nunavut today has no Inuit doctors or dentists, geologists or mining engineers, biologists or soil scientists. There are two Inuit doctors in southern Canada. Born on the trapline, world-renowned thoracic surgeon Noah Carpenter boarded at a residential hostel in Inuvik. He graduated from high school in 1963, before progressive education took hold. And Inuit heart surgeon Donna May Kimmaliardjuk, born in Winnipeg, lived only briefly in Nunavut where her mother’s from, and she was educated in southern Canada.

In communities wracked by homelessness, addictions and suicide, by teenage pregnancy and foetal alcohol syndrome, by crime and incarceration, some 10,000 Inuit youth will be coming of age during the next decade. It’s largely eluded notice, however, that those who are educated and skilled and engaged in or preparing for rewarding employment seldom get into trouble or go to prison. So the high-tech economy, which today includes mining, requires effective instruction, from an early age, that’s oriented toward science, technology, engineering and mathematics—as well as to carpentry, metalwork and mechanics. Nobody appears to know of templates around the world, notably in Asia, for raising Third World peoples into the First in a single generation.

Historically, mining companies established settlements, with corresponding facilities, for employees and their families at the mine site. No longer. Even Baffinland, with its expected mine life of 200 years, flies employees in and out for two weeks on and two weeks off. Given that model, there’s a case for following Joey Smallwood’s example for Newfoundland. He relocated 30,000 people away from outports where the cost of delivering services was unsustainable. Arguably, the cost of sustaining Nunavut is also unmanageable at some $3 billion annually, or about $90,000 for every Inuit man, woman and child.

For marginalized Inuit today, conditions are arguably worse than they were in 1974, when Farley Mowat wrote in preface to his book People of the Deer that they lived in unguarded concentration camps. So why not move to the south and away from remote settlements having no economic reason to exist? It would not be the proverbial rocket science to deliver mentoring and help that works. Today, only immigrants get that. Not the urban Indigenous.

Arguably then, this devolution of power is yet another shell game. Unconscionable conditions will continue for the burgeoning Inuit underclass—and at unsustainable cost to taxpayers.

Colin Alexander was publisher of the Yellowknife News of the North. His most recent book is Justice on Trial: Jordan Peterson’s case and others show we need to fix the broken system.