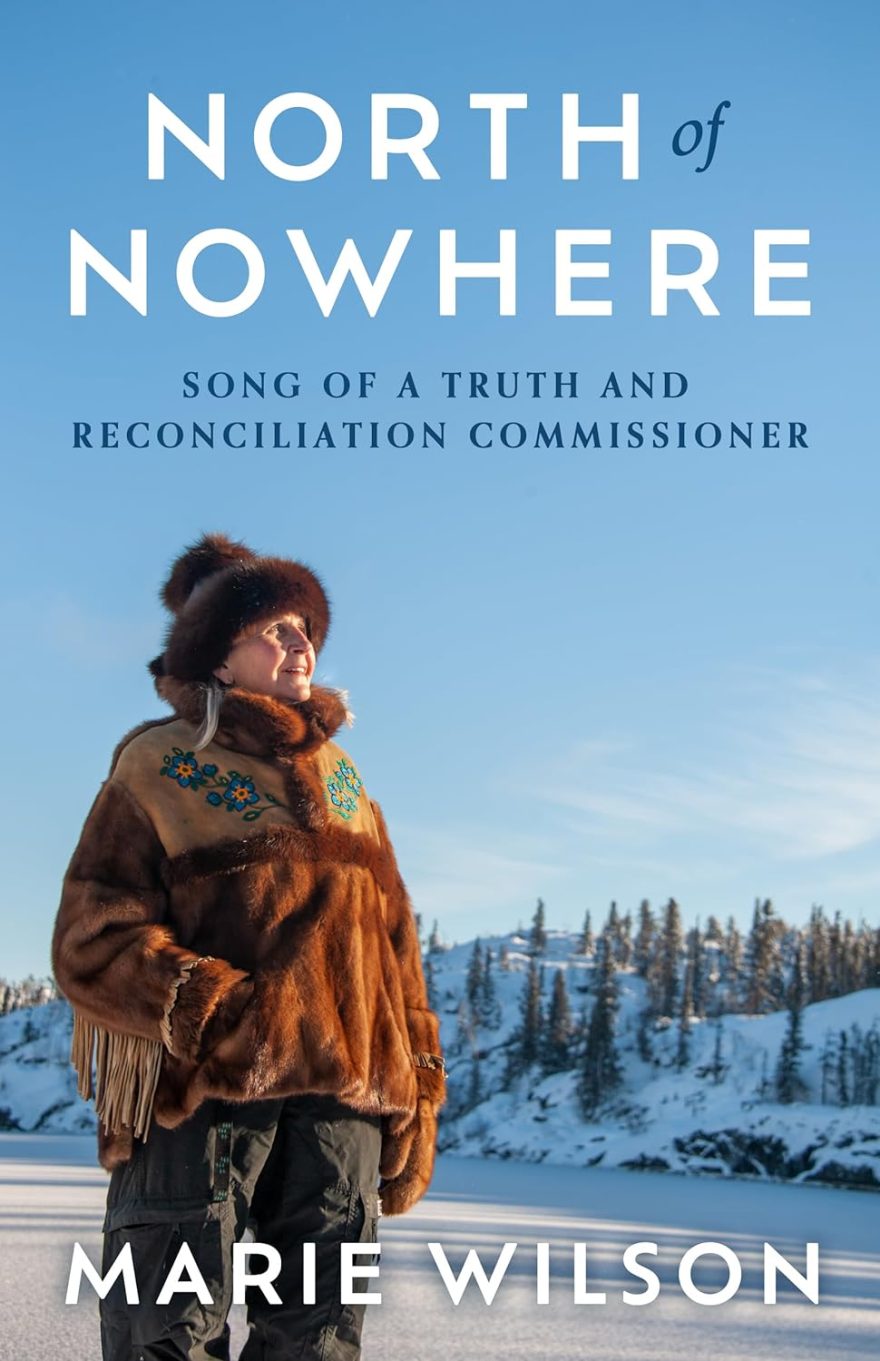

North of Nowhere: Song of a Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner, by Marie Wilson (Anansi Press, 2024, 362 pp. Hardcover $34.99)

A Review by Colin Alexander

This recently published book of reminiscences, by former Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) commissioner Marie Wilson, warrants a review only because she regurgitates widely accepted falsehoods that need to be debunked. Promotion for North of Nowhere erroneously suggests that it represents real history from Canada’s Indian Residential Schools (IRS) inquiry.

But as historian Basil Liddell Hart explains “The object [of history] might be…expressed thus: to find out what happened while trying to find out why it happened. In other words, to seek the causal relations between events.”

Wilson’s book follows three multi-million-dollar, government-funded commissions—RCAP, TRC and MMWG. They delivered no vestige of a workable plan for turning things around for the burgeoning Indigenous underclass. Instead, taxpayers support never-ending make-work projects for self-serving Indigenous elites, the equivalent of the “In Party” in George Orwell’s 1984. As for the corresponding proletariat, I know an Ojibwa grandmother who got a $10,000 compensation cheque for her one-year stay in an IRS. Within a week it went for past and current purchases of crack cocaine. I also know an Inuk who got $95,000 compensation in April 2023. After splurging in Ottawa on drugs, alcohol, and prostitutes, by August he was again scrounging for cigarettes.

Wilson’s stated aim is “to dig up as many witnesses as possible, and cross-reference for consistency….” She admits there was no questioning of those telling their stories nor attempted corroboration of what they said. She throws out “the promise I made to the Survivors of…residential schools…and to the still unknown thousands of little ones that did not survive.”

The TRC report recorded only a single instance where an attendee claimed to have seen a murder. But the RCMP found no substance to the lurid story from Doris Young, who had attended the Anglican Elkhorn Residential School in Manitoba. Whatever the school’s shortcomings, Young earned an honours degree in political science and a master’s in public affairs. Since then, she has held various postsecondary teaching positions. It eluded the Commissioners, including Wilson, that no such opportunities exist in today’s violence-wracked Indigenous communities and urban slums. The elite never advocate for the education, skills training, and opportunities for a rewarding career that they had for themselves.

Wilson calls her husband, Stephen Kakfwi a “Survivor.” Evidently, his attending Grandin College in Fort Smith enabled him to become Premier of the Northwest Territories, as did another Grandin attendee, Jim Antoine. Described as “the school we all loved,” CBC reported on a reunion in 2008 to celebrate the 80th birthday of its Catholic founder, Fr. Jean Pochat-Cotilloux.

In 2014, CBC’s Duncan McCue interviewed TRC Commissioner Wilton Littlechild, who attended the Roman Catholic Ermineskin Indian Residential School in central Alberta: “If I didn’t graduate, what was the alternative?” he asked. “I could have been found dead on the street in Edmonton on skid row, because of alcohol. So, it’s really that strong for me, the influence of hockey in my life.” As an undergraduate in the mid-1960s, he was on the University of Alberta Golden Bears’ hockey team.

Mainstream news media keep repeating the falsehood that TRC Commissioner Murray Sinclair told the United Nations in 2010: “For roughly seven generations nearly every Indigenous child in Canada was sent to a residential school.” In fact, documentary requests by several Indigenous bands exist for the construction of residential schools for which they granted reserve land. School attendance became compulsory only in 1920, but it was not enforced. IRS enrollment peaked in the early 1930s, at about one third of all school-age Indians. By numbers, enrollment peaked in 1958 at about 12,000.

In an interview with CBC’s The Current, Commissioner Sinclair escalated the number of deaths cited in the TRC report from 3,201. Sinclair said “the number of children who died was “as high as 25,000.” After 1945, and the introduction of antibiotics, the number was close to zero. Before then, tuberculosis killed innumerable thousands regardless of race, or social or economic class.

Nina Green’s scholarly research failed to find a single IRS attendee unaccounted for. Nor has Interlocutor Kimberly Murray identified a single name after two years of searching. But Wilson carried forward Sinclair’s apparent invention.

Wilson says she was devastated by the discovery of unmarked graves at the Kamloops Roman Catholic Residential School. Across Canada there are many undesignated cemeteries, and many graves are unmarked because the customary wooden crosses disintegrate. Where graves were said to be in the Kamloops apple orchard, ground-penetrating radar showed only anomalies from soil disturbance. The book Grave Error, published well before publication of Wilson’s book, analyses the available evidence.

As for cultural genocide, Wilson says “killing Indigenous languages was an intentional strategy for killing the transfer of teachings and ties to family.” This belies the fact that many school employees learned and used Indigenous languages. Clergy created dictionaries and orthographies for Indigenous languages, and their translations of the Bible helped to preserve Indigenous cultures. Why, I ask, did TRC slash Helen Harrison’s budget for interviewing former IRS staff and their children, and for transcribing what they said?

You would never know from Wilson’s book that the IRS enabled almost all today’s prominent Indigenous elites to succeed. Nor that the complete TRC report includes expressions of gratitude by former attendees. In fact, the IRS provided a safety net for orphans and children whose families could not look after them. Contradicting Wilson’s assertion that students were reluctant to return, a former supervisor at the (Anglican) Stringer Hall in Inuvik told me of children who were happy to be back at the end of summer. Then they could shower and change their clothes worn since summer began. Elsewhere, there are credible reports of girls reluctant to go home because of constant sexual predation by family members. For perspective on Indian administration of child welfare, read Flowers on my Grave, by Ruth Teichroeb.

Coming back to Liddell Hart, Indigenous history lacks evaluation of the options at the time when decisions were made. Still unresolved is whether to enable next generations as the professionals, artisans and technicians needed in the high-tech economy—jobs the Indigenous youth I talk to say they want. Current orthodoxy calls for self-determination. As envisioned in Karl Popper’s The Open Society and its Enemies—a primer for the values in western democracies that means life within tribal and hierarchical collectives, perpetuating Orwell’s nightmare for the marginalized. And taxpayers.

For fact-based historical analysis, read two other books: Grave Error edited by Chris Champion and Tom Flanagan, and Truth Comes before Reconciliation edited by Rodney Clifton and Mark DeWolf. Wilson’s Song of Truth resembles Hitler’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels’ mission statement, “If you repeat a lie often enough, people will come to believe it, and you may come to believe it yourself.”

Colin Alexander was publisher of the Yellowknife News of the North and the advisor on education for Ontario’s Royal Commission on the Northern Environment. His latest book is Justice on Trial: Jordan Peterson’s case and others show we need to fix a broken legal system.