In his March 2 article, “The cheapest way to cut carbon,” economist Trevor Tombe presents the basic logic of emission taxes as applied to CO2. In theory, a uniform carbon price would minimize the cost of emission reductions because it would prompt emitters to identify and implement abatement options that cost less at the margin than paying the tax. Letting the market find cheap abatement options under the guidance of a uniform price is, in theory, a neat way to cut emissions at the lowest possible macroeconomic cost. Traditional regulatory measures, which economists call command-and-control, cannot accomplish this.

That, at any rate, is the theory. And in theory, as Yogi Berra said, there is no difference between theory and practice, but in practice there is. The problem with the theory of carbon pricing is that, in Canada, the existing policy framework has destroyed the possibility for taxes to achieve efficiency.

The textbook theory assumes that a carbon tax is implemented instead of, not on top of, command-and-control. If command regulations already exist, they first have to be removed before imposing the tax. Otherwise, adding emission taxes does not fix the inefficiencies, it just exacerbates them. So when the Ecofiscal Commission and others call for carbon taxes, they are not contributing to better environmental policy-making; they are proposing to make a bad situation worse.

The existing Canadian policy framework includes a host of command-and-control regulations that have imposed carbon dioxide abatement at far more than any reasonable estimate of the appropriate tax rate. The federal ethanol mandate is one example. A few years ago my colleague Doug Auld and I published a study showing that greenhouse gas reductions from corn ethanol production cost between $400 and $3,300 per tonne. Adding an additional tax on fuel won’t fix that, it will just increase the distortion at the margin.

A 2013 study I did for the Fraser Institute showed that Ontarians were incurring over $4 billion per year in costs related to the Green Energy Act, the centrepiece of which was the move to phase out coal-fired power plants. The province’s underlying scientific study showed there would be almost no resulting improvement in air quality, but it has instead pointed to the approximately 25 megatonne carbon-equivalent reduction in CO2 emissions as the main rationale. At the time of my study the switch to renewables had only resulted in replacement of less than one-third of the generating capacity lost when the Lambton and Nanticoke power plants were lost. Spending $4 billion to eliminate 8 million tonnes of emissions implies a cost of $500 per tonne. Once again, adding a carbon tax (or tradeable permits, as Queen’s Park is proposing) onto the Ontario electricity grid will only amplify these costs without introducing any new efficiencies.

Tombe argues that a national minimum carbon price would be a good idea. A far better idea, however, would be a national maximum carbon price, and a pledge to eliminate all the regulatory abatement measures that exceed it. This would be much closer to what a carbon tax is supposed to do.

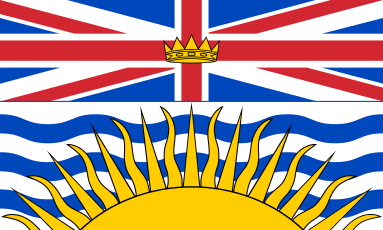

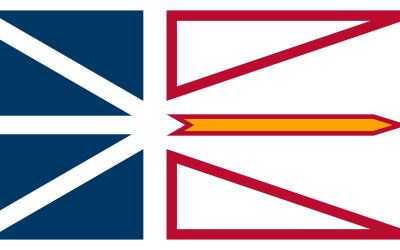

There is no credit in calling for the introduction of carbon taxes if one has not first helped in the much harder task of working for the removal of the policies that created the conditions in which carbon taxes can’t function. I’ll believe the Ecofiscal Commission is serious about improving the economic efficiency of Canada’s environmental policy framework when it starts putting as much effort into publicly criticizing the Notley government’s plan to phase out coal in Alberta, or the federal ban on B.C. coastal tanker traffic, or the Quebec campaign against the Energy East pipeline, as it does into calling for new taxes on Canadian firms and households.

Out of nowhere, carbon pricing has become a political fad. All the government’s favourite experts and beautiful people are on board. But the underlying theory simply does not back up the superficial claims being thrown around. Carbon pricing can help control some aspects of the costs of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but only in some circumstances and not in the ways typically being claimed in Canada.

Ross McKitrick is a professor of economics at the University of Guelph and chair of Energy, Ecology and Prosperity at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.