This article was reprinted from the Wall Street Journal. Access source article here.

Imagine the Arctic in 2050 as a frigid version of Nevada—an empty landscape dotted with gleaming boom towns. Gas pipelines fan across the tundra, fueling fast-growing cities to the south like Calgary and Moscow, the coveted destinations for millions of global immigrants. It’s a busy web for global commerce, as the world’s ships advance each summer as the seasonal sea ice retreats, or even briefly disappears.

Much of the planet’s northern quarter of latitude, including the Arctic, is poised to undergo tremendous transformation over the next century. As a booming population increases the demand for the Earth’s natural resources, and as lands closer to the equator face the prospect of rising water demand, droughts and other likely changes, the prominence of northern countries will rise along with their projected milder winters.

If Florida coasts become uninsurable and California enters a long-term drought, might people consider moving to Minnesota or Alberta? Will Spaniards eye Sweden? Might Russia one day, its population falling and needful of immigrants, decide a smarter alternative to resurrecting old Soviet plans for a 1,600-mile Siberia-Aral canal is to simply invite former Kazakh and Uzbek cotton farmers to abandon their dusty fields and resettle Siberia, to work in the gas fields?

European explorers first started pressing north five centuries ago, searching for an alternate passage to the Orient. By the 19th and early 20th centuries, urban donors around the world were funding expeditions to the Northwest Passage and North Pole. Fears of Japanese invasion and communist ideology opened up the region as military spending poured in during World War II. During the Cold War, American and Russian forces played cat-and-mouse war games there with spy planes and nuclear-armed subs.

Today, scientists studying oil and gas potential—and how shrinking summer sea ice might make it easier to access offshore deposits—are convincing governments and investors that the region has rising strategic value. Private companies have snapped up Canada’s northernmost railroad and port of Churchill, bought $2.8 billion in Arctic offshore energy leases, and begun developing specialized tanker ships and platforms for offshore drilling in icy environments. This year, Russia and Norway resolved a four-decade-long boundary dispute in the Arctic Ocean, which could pave the way to more offshore development. Canada, Norway and Russia are bolstering their militaries with ice-strengthened patrol ships, frigates, attack submarines and fighter jets.

Already, tourism is booming. In response to scientific evidence of climate warming in the region, environmental groups around the world are raising money for, and awareness of, the Arctic. This publicity has spurred a massive increase in tourism to the area. In 2004 more than 1.2 million passengers traveled to Arctic destinations on cruise ships. Just three years later the number more than doubled; by 2008 there were nearly 400 cruise-ship arrivals in Greenland alone. Many passengers cite the desire to "see the Arctic before it’s gone" as motivation for the pricey tickets. And while a liquid Arctic won’t arrive anytime soon, the new tourism companies, port-of-call businesses, and other new stakeholders springing up to meet this demand will.

Research and development is rising too. The U.S. National Science Foundation alone now funnels nearly a half-billion dollars annually to polar research, more than double what it did in the 1990s. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the European Space Agency are developing new satellites to map and comprehend the polar regions as never seen before. NASA’s investment alone will likely reach $2 billion by the middle of this decade.

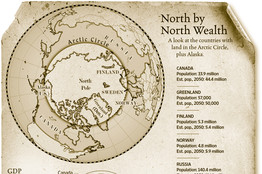

The Arctic proper (northward of the Arctic Circle, approximately 66°33′ N latitude) is actually tiny relative to the outsized attention it enjoys with science funding agencies, commonly used map projections and the public imagination. Only 4.2% of the planet’s surface and 4.6% of its ice-free land (meaning not buried under glacial ice) lie north of this parallel, nearly all of it treeless, deeply frozen in permafrost, and plunged into polar darkness for much of the year.

North of the 45° N parallel, however—lands and seas held by the U.S. (including its long row of northern states), Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia—we find 15% of the planet’s surface area and a whopping 29% of its ice-free land. With their far greater land area, population, biological productivity and economic clout, it is these larger regions—together with their Arctic hinterlands—that form the heart of a "New North," a place of rising human presence and world interest in the 21st century. Such a bloc, if so measured today, would contain over 12 million square miles (more than triple the land area of China), a quarter-billion people, some of the world’s most livable cities and a $7 trillion economy.

The numerous connections among New North countries go well beyond the obvious geographic ones. Despite memberships in the European Union, Sweden and Finland feel greater cultural and economic kinship to Iceland and Norway than to Italy or Greece. Northern indigenous groups, like the Inuit and Sami, both identify and organize across national borders. Since the 1990s, even cantankerous Russia has been forging ties with its northern neighbors, including participation in the Arctic Council, healthy trade with Finland, and an expressed desire to open a shipping lane to Canada’s port of Churchill. The countries of the New North collaborate constantly on issues of fisheries, environmental protection, search-and-rescue and science. They share peaceful, stable borders that count among the friendliest in the world. And contrary to popular perception, their mineral claims to the Arctic Ocean sea-floor are proceeding calmly, even cooperatively, under Article 76 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

The New North is thus well positioned for the coming century even as its unique polar ecosystem is threatened by some of the most extreme climate changes on Earth. But in a globally integrated 2050 world of over nine billion people, with mounting issues of water stress, heat waves and coastal flooding, what might this mean for motivating renewed human settlement of the region? To what extent might a wet, underpopulated, resource-rich, less bitterly cold North promise refuge from these broader global pressures?

North by North Wealth

Such questions demand consideration of what makes civilizations work in the first place. In his book "Collapse," Jared Diamond scours history to ask why civilizations fail. He identifies five key dangers that can threaten an existing society: self-inflicted environmental and ecosystem damage, loss of trading partners, hostile neighbors, adverse climate change and how a society chooses to respond to its environmental problems. Any one of these, Dr. Diamond argues, will stress an existing settlement. Several or all combined will tilt it toward extinction.

Turning the question around, what causes new civilizations to grow? First and foremost will be economic incentive, followed by willing settlers, stable rule of law, viable trading partners, friendly neighbors and beneficial climate change.

At first blush all eight New North countries fulfill these requirements to some degree. Save Russia, they rank among the most trade-friendly, economically globalized, law-abiding countries in the world. They control a valuable array of coveted natural resources. Already, they enjoy more petitions from prospective migrants than they can or will absorb. They are friendly neighbors. Their winters will always be frigid, but less bitterly so than today. Biomass will press north, including some increased agricultural production in contrast to the more uncertain futures facing much larger agricultural areas to the south.

Already the New North possesses a sprinkle of sizable settlements from which to grow. Their biggest hubs—like Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Seattle, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Ottawa, Reykjavik, Copenhagen, Oslo, Stockholm, Helsinki, St. Petersburg and Moscow— are growing fast and attract many foreign immigrants today. Smaller destination cities include Anchorage, Winnipeg, Saskatoon, Quebec City, Hamilton, Goteborg, Trondheim, Oulu, Novosibirsk and Vladivostok. Some truly northern towns that might grow in a New North include Fairbanks, Whitehorse, Yellowknife, Iqaluit, Tromso, Rovaniemi, Murmansk and Surgut.

Cities are key to the New North because, like everywhere else, it is rapidly urbanizing. Even in the remote Arctic and sub-Arctic, people are abandoning small villages or a life in the bush to flock to places like Fairbanks, Alaska; Fort McMurray, Canada; and Yakutsk, Russia. Tiny Barrow, Alaska—a metropolis by Arctic standards—is absorbing an influx of people from remote hamlets across the North Slope. Paired with reduced winter road access and ground disruptions from thawing permafrost, this urbanization trend suggests abandonment of all but the most lucrative of remote interiors.

Outside the cities and towns it’s hard to attract new settlers, especially in the Arctic hinterlands. With four million people and a gross domestic product slightly larger than Hong Kong’s, the circumpolar Arctic holds a bigger population and economy than most people realize, but both are still fleetingly small. For example, with just 57,000 people and $2 billion gross domestic product per year, Greenland’s population and economy are 1% of Denmark’s. Furthermore, the mainstay of the Arctic economy is simply exporting raw commodities like metals, fossil fuel, diamonds, fish and timber. Public services comprise the second-largest sector, followed by transportation. Tourism and retail are significant only in a few places. Universities are rare, and manufacturing extremely limited except for a robust electronics industry in northern Finland around the city of Oulu (Nokia is one of the better-known companies operating there).

Thus, the Arctic economy is a restrictive blend of resource-extraction industries and government dollars, with an underskilled and undereducated work force. Most of these natural resource profits leave the far North, creating an apparent "welfare state" situation in which central governments prefer to deeply subsidize public services rather than surrender profits to local taxation.

Career choices are limited and although salaries are high, so is the cost of living. One can expect to pay $250 per night for a cheap hotel room and $15 for a cheeseburger in an Arctic town. Gas pipelines and diamond mines generate enormous wealth, but most of this revenue flows south (or west, in Russia), controlled by an array of private, multinational, and state-owned actors and central governments. In North America, much of what’s left is controlled by indigenous-owned business corporations and/or regulated through a wave of comprehensive land claims agreements, now nearly complete, that return substantial political power to the region’s original occupants.

Put simply, the Arctic is not an easy place for fresh arrivals and business start-ups outside of a narrow range of activities. Add to all this the infernal cold and darkness of the polar winter, followed by the steaming heat and billions of mosquitoes of the polar summer, and we see the Arctic will never be a big draw for southern settlers. Even the sub-Arctic hydrocarbon boom cities of Fort McMurray; Noyabr’sk, Russia; and Novy Urengoy, Russia, must recruit heavily to attract enough foreign workers. While Arctic settlements will grow with the region’s rising energy, mining and shipping base, its fast-growing indigenous population (in North America), and the ongoing urbanization trend, it’s hard to imagine big new cities spreading across it by 2050 or even 2100.

Instead, a better envisioning of the New North today might be something like America in 1803, just after the Louisiana Purchase from France. It, too, possessed major cities fueled by foreign immigration, with a vast, inhospitable frontier distant from the major urban cores. Its deserts, like Arctic tundra, were harsh, dangerous and ecologically fragile. It, too, had rich resource endowments of metals and hydrocarbons. It, too, was not really an empty frontier but already occupied by indigenous peoples who had been living there for millennia.

Flying over the American West today, one still sees landscapes that are barren and sparsely populated. Its towns and cities are relatively few, scattered across miles of empty desert. Yet its population is growing, its cities like Phoenix and Salt Lake and Las Vegas humming economic forces with cultural and political significance. This is how I imagine the coming human expansion in the New North. We’re not all about to move there, but it will integrate with the rest of the world in some very important ways.

I imagine the high Arctic, in particular, will be rather like Nevada—a landscape nearly empty but with fast-growing towns. Its prime socioeconomic role in the 21st century will not be homestead haven but economic engine, shoveling gas, oil, minerals and fish into the gaping global maw.

—From "The World in 2050" by Laurence C. Smith, to be published by Dutton, a member of the Penguin Group, on Sept. 23. Copyright © 2010 by Laurence C. Smith.

map by Joe Lemmonier

map by Joe Lemmonier Kevin Cooley/Redux

Kevin Cooley/Redux