Yad Vashem means “a memorial and a name.” Though I am not a Jew, I nevertheless add my name of Lee Harding and my memories of my visit. My visit in 2009 to the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem has left an enduring impact on me. The largest lasting impression was not the imposing structure designed by Canadian-Israeli architect Moshe Safdie, nor the displays therein. It was our tour guide, whose name I forget, but whose words have stuck with me. I feel she not only told me about the past, but a horrible future possibility.

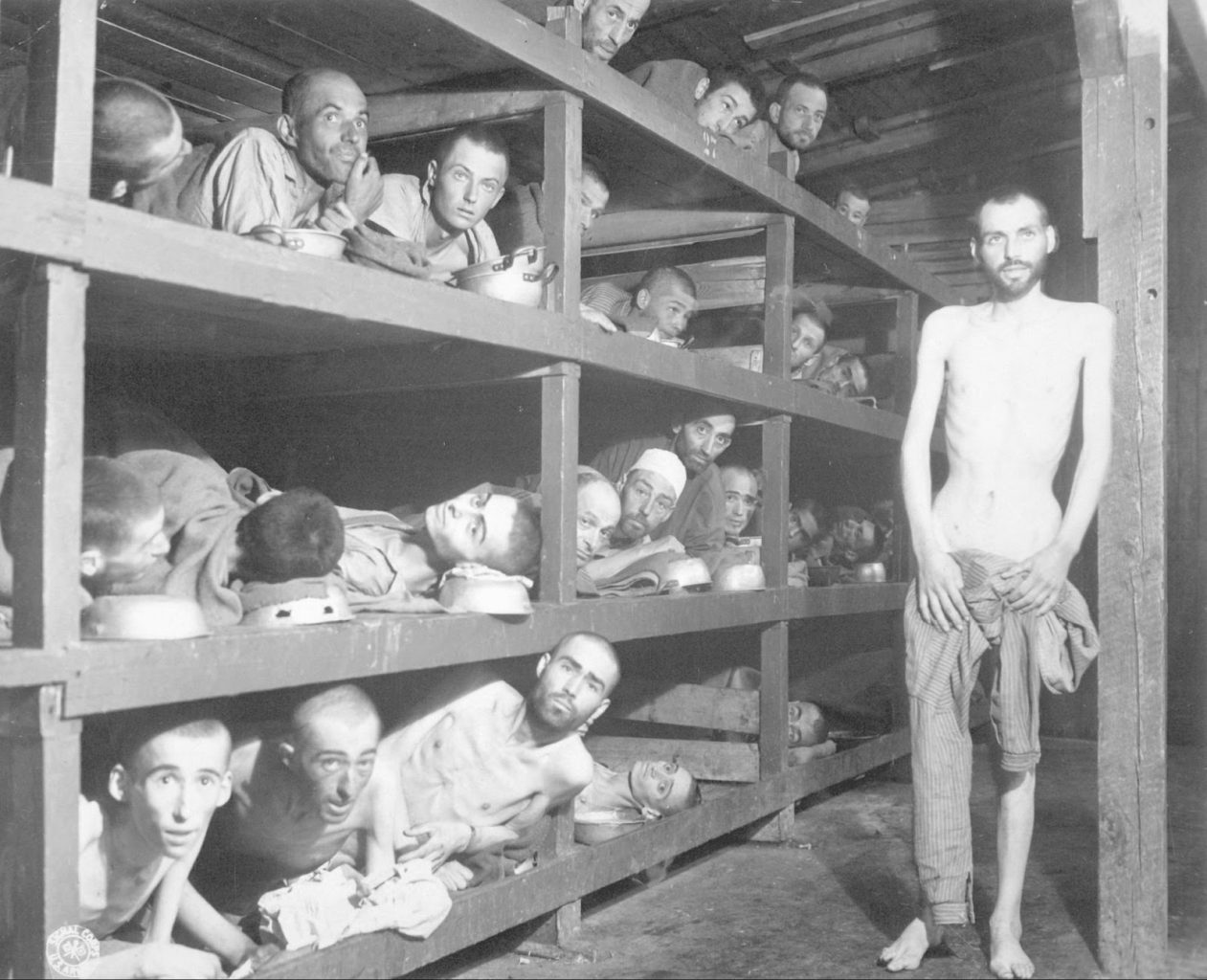

In our times, some loudly proclaim their victimhood from systemic discrimination, but many holocaust victims, who had the clearest claim to such suffering, were remarkably quiet about it, even to their own family. This came dramatically to light after our guide showed us a picture of Elie Wiesel. The famous Romanian-American Jew, prolific author, and Nobel Laureate was photographed at the Buchenwald concentration camp on April 16, 1945, five days after its liberation. Wiesel is in the second row from the bottom, seventh to the left, next to the bunk post, just one of many gaunt prisoners who slept three to a bunk.

(Source:https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/dc/Buchenwald_Slave_Laborers_Liberation.jpg)

The photo is on display at Yad Vashem, and as our tour guide discussed it, she shared the story of two women she discussed the picture with to a previous tour group. One woman exclaimed to another family member, “Look, it’s grandpa!” Their grandfather had been Elie Wiesel’s bunk mate, but never told his family. The tour guide also shared that on another occasion someone found their great uncle in the same photograph. These were tangible examples of “a memorial and a name.”

Why were Shoah survivors so quiet? Liliana Segre, an Auschwitz survivor, tells us it was just easier that way. Of the 776 Italian children sent to Auschwitz, Segre was one of the fortunate 35 who survived. Three times, guards selected who lived and who died, and somehow she was always chosen to live. She told Euronews in January of 2020:

Almost all those who returned didn’t say anything for a long time. It was very difficult to find the right words to describe what we went through. It is almost impossible for those who have not experienced and suffered what we have, to understand what we did, and the differences between us and them, coming back to a normal life.

I was a silly teenager. I was just 15 years old when I got back, and found my old friends, and what was left of my family. I was so different to them. I decided that silence was the best choice. Heavy silence. It was not easy, but it was better than talking about it and not being understood.1

My guide shared another curious detail of the death camps that stuck in my mind. The impending death of victims was concealed to the very end. But why?

In 2019, author Nestar Russell drew some conclusions on this question his book chapter, “The Nazi’s Pursuit for a ‘Humane’ Method of Killing.” He summarized the Nazi method this way: “First, victims should remain totally unaware that they are about to die. Second, perpetrators need not touch, see, or hear their victims as they die. Third, the death blow should avoid leaving any visual indications of harm on the victims’ bodies. And finally, the death blow should be instantaneous.”2

If the perpetrators thought they were cruel to be kind, they were wrong. How sad and awful it is to read Russell’s accounts of the “elaborate props of deception. These included . . . promises of water, food, and work after taking a quick shower, fake railway stations, pleasantly painted gas chambers with flowers and a carefully placed Star of David.”

In Russell’s view, the “smooth and efficient flow of victims” was only one reason the Nazis went to such lengths. Strange as it may seem, the rest of the impetus was to make death psychologically easier for victims and killers alike.

Russell writes, “When, as survivor Ada Lichtman noted, the props of deception encouraged victims to dance, sing, and applauded on their way to the grave, perpetrators would have found the psychological stress associated with being an executioner much easier to bear.” And, “for the victims, the elaborate deception would make for a less stressful and therefore more ‘humane’ dying experience.”

Of course, many in the camps were not fooled by these deceptions. Some even escaped to tell. Our guide also shared the remarkable truth that many refused to believe the testimony of those who escaped the camps. The cost of their disbelief was usually death.

In 2001, Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum interviewed Marek Edelman and Simcha Kazik, two Jews who lived in the Warsaw ghetto in 1942. Berenbaum asked what they’d known about the camp at Treblinka, where many Jews were taken on trains. Edelman said the real issue was Chelmno, which opened over eight months before Treblinka did.3

Two men had escaped from Chelmno and warned of “mobile gas vans killing people with exhaust fumes.” Warsaw Judenrat [Jewish Council] leader Adam Czerniakow reportedly thought “it was impossible that such a thing could happen in Warsaw.” Common Jews reasoned, “There is a war . . . Germans need a big labor force. There is no reason to kill them.” Whatever logic there was to this thinking, there was also denial.4

From July 22, 1942 to September 12 of that year, 265,000 Jews were taken from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka, supposedly for “resettlement.” As this began to happen, Jews wanted to know more about what awaited them. Zygmunt Frydrych, a member of the resistance, boarded a train of his own accord to find out. At the Malinka stop nearby the camp, railway men confirmed to Frydrych that the trains arrived full and left empty. Worse, no provisions were made for food, no wells had been dug, and the camp was silent.5

The next day, Frydrych found a dazed man walking with nothing but his underwear. He turned out to be a friend named Walach. He had escaped the camp and recounted the gassing and executions in detail. Even then, Frydrych wanted some way to return to Warsaw with his own first-hand confirmation. “Take a deep breath,” Walach told him. Frydrych instantly recognized the smell of burning flesh. He returned to Warsaw with the task of convincing those in the ghetto that the trains took Jews to their death.6

As it turned out, Frydrych was dead within a year. In May of 1943, he smuggled Jews out of Warsaw and brought them across the Vistula river to Pludy. However, a Polish man who had promised them shelter in his home reported them to the police. They were led through the town with signs on their chest that read, “Jewish bandits will be shot. This is how we deal with Jews and those who help them.” They were shot beside a fence that faced the house where they thought they would be sheltered.7

The tour guide told us how Nazis used photos and film from the Warsaw ghetto to propagandize Germans. Some images showed Jews living in opulence, drinking and playing cards, sunbathing in the streets, or attending theatre. Other images showed poorly clothed and starving Jews in the streets. The juxtaposition inspired contempt for Jews who, it seemed, did not care for their own selves.8

The scenes of high-living were misleading, often portrayed by paid actors. The plight of impoverished Jews was real enough, but not due to self-neglect. The people had been restricted into walled ghettos where they wasted away and typhoid and lice were rampant. The average food ration for Warsaw Jews was 184 calories, compared to 699 calories for Poles and 2,613 calories for Germans.9

Our guide also shared about the world’s unwillingness to take in Jewish children and refugees, such as those on the St. Louis ship.10 Hitler took it as an opportunity to say that if the rest of the world didn’t want Jews, the world should not complain about Germany’s choices regarding them.11 Sometimes we must ask individually and collectively if we have really done all we could for our fellow human.

“And remember, this all happened in a democracy,” warned our guide. That may be the most disturbing fact of all. History tells us the progression. In 1923, Hitler and the Nazis gathered a private army of 15,000 stormtroopers and attempted a coup in Bavaria.12 Hitler was sentenced to a year in jail and there he wrote Mein Kampf. In 1932, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor of Germany, since the Nazis had more members elected to the Reichstag than any other. Shortly thereafter, a fire broke out in the Reichstag building. A Dutch communist confessed to starting it.13

Hitler convinced Hindenburg to declare an emergency decree to suspend civil liberties, including the freedoms of assembly, expression, and the press. Citizens could be detained without charges. Political opponents were jailed or killed. When Hindenburg died, Hitler assumed the titles of chancellor, führer, and commander in chief of the army. The army expanded and conscription was reintroduced.14 The pressure of crises and the manipulation of events led to an unexpected result—at least to most observers.

This could all happen again. As Yale history professor Timothy Snyder wrote, “There is little reason to think that we are ethically superior to the Europeans of the 1930s and 1940s, or for that matter less vulnerable to the kind of ideas that Hitler so successfully promulgated and realised.”15 The right (or more properly wrong) leadership could seize control in difficult circumstances, claim unusual powers in pretense, propagandize the people to support the government, and systemically kill opponents in a manner so heinous that people will refuse to believe it is even happening.

Over 131,000 survivor testimonies, 500,000 photos, 4.8 million names, and 210 million pages of documentation are housed at Yad Vashem.16 Yet, a “memorial and a name” must not only be in the heart of every Jew but also of every person everywhere. Each one of us shares in the responsibility to prevent another holocaust from occurring in our time.

Lee Harding is a research associate with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

[show_more more=”SeeEndnotes” less=”Close Endnotes”

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4omVqX67oI

- https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-97999-1_8

- https://www.facinghistory.org/holocaust-and-human-behavior/chapter-9/what-did-jews-ghettos-know

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- http://www.eilatgordinlevitan.com/warsaw/w_pages/warsaw_stories_blones.html

- https://youtu.be/wgB8EgiBcLw?t=1155

- https://archive.org/details/courageundersieg0000rola/page/99

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/ms-st-louis

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/refugees?series=48599

- https://www.history.com/topics/germany/beer-hall-putsch

- https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/how-did-hitler-happen

- https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/how-did-hitler-happen

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/16/hitlers-world-may-not-be-so-far-away

16. https://www.yadvashem.org/archive/about/our-collections.html

[/show_more]

Photo by MARCIN CZERNIAWSKI on Unsplash.