Teachers in more than 40,000 classrooms across Canada are providing their students with false information about the tragic death of young Chanie Wenjack whose frozen body was found curled up beside a railway track in northwestern Ontario on October 23, 1966.

The primary source of the misinformation is Gord Downie and Jeff Lemire’s Secret Path.

Despite the fact Chanie Wenjack was attending a public school in Kenora and only boarded at the former Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School along with 149 other Aboriginal children from far-away reserves without schools, Secret Path shows them praying at classroom desks with a nun looking on.

There were no nuns at Cecilia Jeffrey. The former residential school was operated by the Women’s Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church.

Nevertheless, school children reading Secret Path see drawings of nuns in habits delousing naked Ojibway boys who are covering their genitals with their hands. A male with a large white cross on his chest drags a screaming child into a building. A nun in a habit pulls a half-naked boy’s ear and makes him yell in pain.

Nothing that was written or said at the time of Chanie’s death suggests that he was physically and/or sexually abused while he was boarding at Cecilia Jeffrey. Nor is there anything suggesting physical and/or sexual abuse in the section about him in the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

Secret Path clearly implies that he was.

Gord Downie’s lyrics say: “I will not be struck. I’m not going back.” What appears to be a pedophile in a clerical collar with a white cross on his chest approaches Chanie’s bed. The young boy looks up with a fearful look on his face.

As a shivering Chanie is shown shuffling along the railway tracks in an unsuccessful attempt to reach his far-away home, an imaginary male in clerical collar with a white cross on his chest looks menacingly through the trees.

Gord Downie’s lyrics say: “I heard them in the dark. Heard the things they do. I heard the heavy whispers. Whispering, ‘Don’t let this touch you’.”

Children learning about the residential schools through the lens of Secret Path in classrooms across Canada appear convinced young Chanie was sexually abused.

One of the Grade 6 students at Saskatchewan’s Pilot Butte School in the photo below wrote Gord Downie’s lyric “Don’t let this touch you” on a drawing showing an apparent victim of sexual abuse.

Grade 5 students at Toronto’s Dundas Junior Public School are also among the thousands of impressionable children across Canada learning about the Indian residential schools through Secret Path.

Here are a few excerpts from letters they wrote to the Wenjack family after their teacher led them through the book.

“I have heard Chanie’s story and I was mad and sad. I think that the government should do something about repaying the First Nations because no one had done anything about it and it was wrong.”

“Chanie’s story has impacted our lives and we want change…If we continue to educate kids and adults all around the world history will not repeat itself.”

“It was really, really, sad to think that a group of people thought kids should be taught in a certain way. I don’t think anybody should ever go through that.”

Those impressionable young minds had no way of knowing what they were being taught is a total misrepresentation of what actually happened to the young Ojibway boy who has now become a national poster child for all that was wrong with the Indian residential schools – despite the fact he was attending a public school at the time of his death.

The back cover of Secret Path says young Chanie died “trying to escape the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School.”

However, there was no evidence of any prison-like or abusive conditions from which he would have had any reason to “escape”.

He had made no attempt to leave Cecilia Jeffrey during the three years he was there – although he did play hooky one afternoon a week before the start of his fateful journey.

Colin Wasacase, a Cree/Saulteaux who had attended residential schools as a child and taught at them as an adult, was in charge of Cecilia Jeffrey at that time. His wife was the matron.

On September 24, 1966 – a month before Chanie’s death — he wrote a letter to Giollo Kelly, Executive Director of National Missions, Women’s Missionary Society, in which he said: “The weather has been beautiful for the past two weeks and the children have been taking advantage of it by staying away from school and wandering away from the premises. The wanderers have been many. Their reasons all stem to loneliness and various other reasons. We do hope that they will all soon recover from it and settle into the school situation as the year progresses.”

On September 29, 1966, he wrote again saying: “The children have begun to settle down a bit. There are only a few girls who persist that school is the worst place to be at ages 12-15 as they feel it isn’t any good. We are having difficulty to convince them that this is not so.”

On September 30, 1966, Giollo Kelly wrote to Colin Wasacase and said: “I can well understand that the beautiful fall weather is making the children very restless. I recall being at the school during the month of June a few years ago when it was very difficult to get the youngsters in for their meals. It was the kind of weather which must have made them think of home. I realize that it will be a very trying period for the staff and I do trust that while we do not hope for poor weather they will soon become accustomed to the routine of the new school year.”

In a letter dated March 21, 1967, Mr. Wasacase wrote: “The students have not fully settled down as yet [after returning from the Christmas break] especially on the girls’ side. A few of the girls have been wandering away from the school but with no real intent of running away home but only to visit friends or hang around town. These are a few who have started a few more. We are hoping that they will become settled.”

Clearly, there was nothing prison-like at Cecilia Jeffrey. The children wandered at will.

On the sunny afternoon that Chanie left, he had been playing on the swings in the playground with two orphaned brothers. One of the brothers had run away three times in the last few weeks and the other skipped class on a regular basis.

The brothers decided to go and visit their uncle at his cabin which was about 30 kilometres away.

Chanie’s best friend testified at the November 17, 1966, coroner’s inquest that Chanie was lonesome and “when the other ‘guys’ were running he decided to go along.”

According to the Kenora Miner and Daily News: “Wenjack was really lonesome, the [public school] teacher said, and on one occasion told him that he longed to return to his home in the north where he was happy with his family.”

The newspaper quoted Colin Wasacase as saying: “The boy had plenty of warm clothing but left in just light apparel.”

According to the TRC report, Colin Wasacase took immediate action when he learned that Chanie was missing. After canvassing other students about where the boy might have gone, “[Wasacase] then travelled to Pine Point and Rabbit Lake in the Kenora area in search of the boy and his companions. Indian Affairs official P.C. Clarkin had gone to Rat Portage and Keewatin in search of the boys.”

It wasn’t until five days after leaving the Cecilia Jeffrey playground with the two orphaned brothers and hanging out with them and his best friend at their uncle’s cabin that Chanie decided to walk to his parents’ home at the fly-in Ojibway community of Ogoki Post on the Marten Falls reserve.

According to the report in the Kenora Miner and Daily News: “There [at the uncle’s cabin] they were fed, cared for and enjoyed trips to a trap line with the uncle. After a few days the Wenjack lad took his departure and started to walk along the single-track C.N.R. right of way.”

His friends’ uncle had shown him how to get to the railway tracks that would take him there and told him to ask railway workers for food along the way. That was the last time anyone saw him alive.

At 11:20 a.m. on the morning of Sunday, October 23, 1966, the engineer of a westbound freight train spotted Chanie’s frozen body curled up at the side of the tracks.

He had walked a little more than 19 kilometres through snow squalls and freezing rain wearing light, soaked-through, cotton clothing. Evidence of how he must have fainted and fallen as he stumbled along the rough railway tracks was found in bruises on his shins, forehead and over his left eye. A pathologist later concluded he had been dead for 24 hours. His stomach was empty, his lungs full of bacteria.

After the autopsy, Chanie’s coffin, accompanied by his three younger sisters who had also boarded at Cecilia Jeffrey, was returned to his home at Ogoki Post. Colin Wasacase – who was recognized as an outstanding Ontario senior citizen by Lieutenant Governor David Onley in 2012 and currently serves as a Kenora city councillor – escorted them on the long journey home.

In a letter he wrote to Ms. Kelly on November 17, 1966, Colin Wasacase said they identified Chanie’s body at the hospital on the evening of the day he was found. Meanwhile, the police were trying to contact the parents.

A couple who knew the sisters well came to Cecilia Jeffrey on Monday to tell them their brother was dead.

“We felt that both Mr. & Mrs. Robinson knew the children better than we and we felt maybe they would comfort them more easily than us,” Mr. Wasacase wrote. “We at this time are still partial strangers to the children as we slowly get to know them better.”

He had taken over management of Cecilia Jeffrey less than four months before Chanie’s death.

Mr. Robinson contacted Daisy Wenjack who was at Red Lake and she was taken to Ear Falls by a minister from Red Lake. The Robinsons met Daisy at Ear Falls and took her to Cecilia Jeffrey.

“In the meantime an older sister Margaret contacted us from Sioux Lookout. We were also finally able to get in touch with the mother at Sioux Lookout hospital Monday night.

“The mother at this time advised that she wanted the body returned home. We took all the children to see the mother Tuesday Oct. 25/66 as she requested she would like to see them.”

Mr. Wasacase said police and Indian Affairs were having difficulty contacting the father at the fly-in community of Ogoki Post.

Mr. Wasacase and the three sisters left by train for Nakina with Chanie’s coffin on Tuesday evening.

Chanie’s mother and sisters Margaret and Daisy boarded the train at Sioux Lookout and joined them at Nakina.

They spent Tuesday night at a hotel in Nakina and left for Ogoki Post with two planes on Wednesday morning.

Rev. J. Long, an Anglican minister from Nakina. had joined them to officiate at Chanie’s funeral.

“The father was very upset as no messages had been received by him until the day of the arrival,” Mr. Wasacase wrote. “I had also written him a letter Oct. 11/66 telling him that his family were all fine. It was after this time that Charles ran away. The father felt that I wasn’t being honest with him and held me responsible for his son’s death, due to my letter saying all was well.”

When the family viewed Chanie’s body during the graveside ceremony, they noticed the stitches from the autopsy and concluded that someone must have stabbed him.

“So they were not going to allow the boy to be buried or my return [emphasis added] until somebody phoned the O.P.P. and confirmed what I had said about an autopsy,” Mr. Wasacase wrote.

When they got through to the OPP on the radio phone, they were assured that Mr. Wasacase had told them the truth about how Chanie died.

After the funeral, the father exercised his rights and said he was not going to allow Evelyn, Annie or Lizzie to return to Cecilia Jeffrey.

The back cover of Gord Downie and Jeff Lemire’s Secret Path says: “Chanie Wenjack (misnamed Charlie by his teachers).”

However, in media interviews and talking about him with school children, Pearl Wenjack calls her brother “Charlie”. According to a nationally-known Indigenous writer/scholar, who does not wish to be named at this time, the family always called him Charlie.

Here is a picture of his gravestone in the cemetery at Marten Falls First Nation.

In a column published in newspapers across Canada, WE Charity co-founders Craig and Marc Kielburger said Chanie Wenjack “died fleeing his residential school” and encouraged Canadians to donate money in support of “Legacy Rooms” in restaurants, schools, libraries and corporate boardrooms.

“For a $5,000 donation,” they wrote, “the Downie-Wenjack Fund will provide an official plaque and signage explaining Chanie’s story to set the tone for the Legacy Room. The money raised supports initiatives to teach about residential schools in Canadian classrooms.”

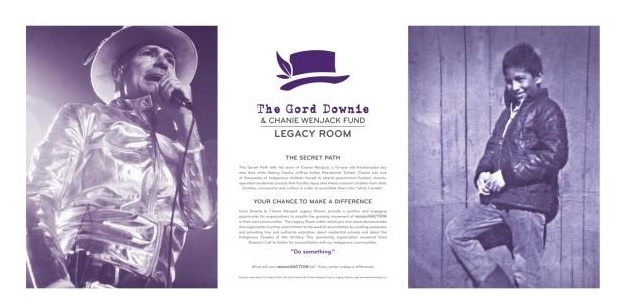

Gord Downie gets top billing on the $5,000 plaques in Legacy Rooms that are now sprouting up across Canada. His trademark hat sits atop the words “The Gord Downie” in boldface. The line below in smaller, lighter, type says: “& CHANIE WENJACK FUND.” There’s a photo of Gord Downie performing at one of his concerts on the left side of the plaque and one of a shy, smiling little Chanie on the right.

One might well ask whose “legacy” is being commemorated. Chanie Wenjack’s name is completely overshadowed.

The plaque looks like part of a donor-supported promotion for the late Gord Downie’s solo albums.

On October 28, 2017, the Globe and Mail published an article about a Canada 150 reconciliation journey through the Northwest Passage on the Polar Prince.

At one point, Aluki Kotierk, president of Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. broke down in tears during a group discussion on reconciliation in the ship’s Legacy Room.

“I just don’t know why in this Legacy Room there is no box of Kleenex,” she said prompting laughter from her colleagues. “Or why Gord Downie’s name is bigger than Chanie Wenjack’s” on the plaque on the wall.

Good question.

About the Author

Toronto author Robert MacBain has been involved with the Aboriginal file for more than 50 years. He was a senior reporter at major Canadian newspapers in the 1960s and a consultant to the Department of Indian Affairs in the early 1970s. He is the author of Two Lives Crossing and Their Home and Native Land and is currently writing two books simultaneously – one on the Indian residential schools and one of the 2006 Mohawk protests/blockades at Caledonia, Ontario, and the costly aftermath.

Read the PDF version here: EF12MisinformationWenjackMacBain