In recent years, there has been a dramatic rise in the number of Canadians who are entitled to claim and receive benefits that go along with holding “Indian status”. All indications are that this trend will continue—and probably accelerate—in the next few years.

These changes will have profound implications for our country.

Let me explain why.

A status Indian (also called “registered Indian”) is entitled to special financial benefits to which other Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians do not have access. These entitlements can include a complete income tax exemption if the person works on a reserve and lives elsewhere or works elsewhere and lives on a reserve. For example, there are city office buildings that are now called sub-offices of Band offices on reserves so that status Indians who work in those offices do not pay income taxes.

Status Indians also receive other benefits that other people do not receive, for example, many young people receive post-secondary education benefits, which includes grants to pay for tuition, books, and room and board.

Simply put, status Indians—even those earning hefty salaries—might not have to pay any income tax, or even sales taxes. In addition, they might be able to have all of their children’s college or university expenses paid by their Band, with money that ultimately comes from taxpayers.

Such benefits are very strong incentives for people to become status Indians. Consequently, more and more people are now applying to become status Indians.

In 1876, The Indian Act was passed by the Federal government, applying the term “status” to First Nations people living in Canada. The legislations implemented soon became very controlling on their everyday lives. This created a dependence on the government. Financial benefits were gradually added to the entitlement of those who were status Indians, making it a more desirable designation.

The number of status Indians in Canada is on the rise, and the birth rate accounts for only a part of the increase. In 1985, the Indian Act was amended to allow Indigenous women who had married non-Indigenous men to apply to regain their Indian status.[i] On Nov 7, 2017, the federal government put forward legislation that will allow the children of women who lost their status and died before the 1985 legislation to pass on their Indian status to their offspring in the same way that status Indian men were able to.[ii]

Moreover, there are a number of gender equity cases that are now being adjudicated by the courts and they have the potential to add many more status Indians to the list. As well, the Daniels case would potentially add many people claiming Metis status to the Indian list.[iii]

Success in these cases will certainly give rise to additional cases coming forward in the future. All-in-all, the combination of court cases and changes in government policies have the potential of adding hundreds of thousands of people to the list of Canadians who are entitled to status benefits.[iv]

In fact, the Indigenous Affairs Minister stated that one version of Bill S-3–the bill to amend The Indian Act to end sex discrimination before the 1982 constitution–could add as many as two million new people to the list of people entitled to those who receive benefits because they have Indian status.[v]

What does Statistics Canada say about Canada’s current aboriginal population?

This government agency reports that between 2006 and 2016, the self-identified Indigenous population grew by 42.5 percent, from 1,172,790 to 1,673,785.[vi] At 587,545, the self-identified Metis population is the fastest growing segment of the Indigenous population, increasing by 51 percent over the last decade. The non-status population of Indigenous people grew by 75.1 percent.[vii] Interestingly, most of the Indigenous population do not live on First Nation’s reserves.

Because the rewards are so great, it is impossible to predict how many more Indigenous people will seek status in the future. Recently, for example, the federal government opened up applications to people in Newfoundland who claimed descent from Mi’kmaq Indians who had, lived seasonally on the island. No more than 10,000 people were expected to apply for status, but the number applying was well over 100,000 before the government became concerned and tried to slow the tide of applicants down.[viii]

The fact is that five hundred years of intermarriage between Indigenous and mainstream Canadians have produced a huge number of potential applicants for Indian status, and we simply don’t know how many of our fellow citizens will seek, or will be granted, status. What is clear is that the number will be large.

These people may be seeking Indian status for many reasons, but the financial benefits are certainly an important reason.

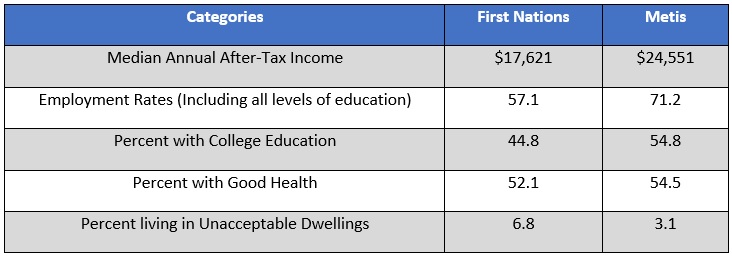

The fact that Metis and other Indigenous people who chose not to isolate themselves on reserves have done far better, in both economic and health terms, than those who live on isolated reserves, has not deterred them. The Figure below shows the differences between Metis and First Nations people.

Even some Indigenous politicians are concerned that so many new people are seeking status benefits. In response to a CBC News report that the self-identified Metis population of Manitoba had increased rapidly, Manitoba Metis Federation President David Chartrand expressed concern that many of the new claimants were seeking Metis status primarily for financial benefits, to the detriment of people, like himself and others, who had worked long and hard to achieve what they saw as the just goal of righting past wrongs.

The process of determining the list of people who should receive special financial benefits from the government will likely take a long time to resolve.

Even so, the dramatic increase in the number of new status claimants will negatively affect the country in many ways. For this reason alone, all Canadians, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike, should pay attention to what is going on.

In the first place, if a select group of people receive very expensive supplemental benefits, it means that mainstream Canadians–those who are not eligible for the same benefits–must pay for the benefits. This will include Canadians who are earning less than some of the people who will be entitled to the benefits.

The blatant unfairness of this process is already causing unhealthy divisiveness in our country, which will become a lot worse as more people are added to the list of those people who are entitled to special benefits. Essentially, there are, or will be, two categories of people: those who will be exempt from taxes and on the receiving end of rich benefits, and those who are not entitled to the benefits, but will be on paying end. This is a sure recipe for a divided country.

Many of the people seeking benefits are non-reserve residents who have more-or-less merged with the mainstream long ago–they are descendants of Indigenous people who left reserves seeking a better life. It can reasonably be expected that their special status benefits will cost significantly more than those on reserves who will take advantage of the benefits, many of whom are on welfare or in low-paying jobs.

It should be remembered that John A. Macdonald gave people a choice when the Indian Act was passed in 1876. Indigenous people could choose to isolate themselves on reserves, or they could become “enfranchised”. This meant that they would receive compensation for lost rights, but from that point on, they would have the same status as other Canadians. At the time, not many Indigenous people chose the enfranchisement option, but today a large number of Indigenous people have simply drifted away from the reserves, seeking better opportunities, living like other Canadians paying taxes and paying for their children’s post-secondary education. Recent evidence suggests that those people who have integrated into mainstream society have done far better than those people who still live on First Nation’s reserves..

Frankly, it is hard to blame people for applying for status. If anyone had the chance to receive gratis the many thousands of dollars that could pay for our children’s college and university education costs, and also be eligible for medical benefits and tax exemptions, we would probably apply.

But, if all these people get what they want, how will it change the country?

Already, we have well-heeled people with status Indian benefits living in cities and paying no taxes. Is it inconceivable that astute Indigenous residents of cities, like Winnipeg, Montreal, or Vancouver will establish tony subdivisions on Indian lands within the cities (so-called urban reserves) or on reserve land adjacent to the cities where the people will work in the cities, but live tax free? Canada has some very clever tax lawyers, and it is not that difficult to see how these arrangements could be made with chiefs and Band Councils.

And even if everything is on the up-and-up, which if history is a guide, it is not likely to be, the yearly cost of all the additional benefits to all the additional people will become truly staggering. The tax burden for ordinary Canadians will become enormous. One begins to wonder what services to other Canadians will be cut to pay for this largesse? (And what services are already being denied to all Canadians, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike, due to this unfair disbursal of money taken from them as taxes?)

The sad thing about these special entitlements is that if all the money now being disbursed or made exempt from tax was actually solving the problem of aboriginal poverty, fair-minded Canadians would not begrudge the taxes. But this is not happening. Chronic unemployment and poverty on First Nation’s reserves and in the inner city remain the norm for the Indigenous underclass. The staggering sums of money required to pay for the special financial entitlements are not solving the problem at all.

A recent survey done for the federal government came to the astounding conclusion that despite the massive federal government increases since 1981, there has been no appreciable improvement in median income of the reserve residents.[ix] poor underclass of Indigenous people are simply being warehoused at government expense, with increasing rates of drug and alcohol dependencies, teenage pregnancies, and suicides.[x] At the same time, increasing financial entitlements will be going to wealthier Indigenous people who are able to look after themselves, as other Canadians need to look after themselves.

This spectacular unfairness is already gnawing at the fabric of Canadian society. I believe that Canadians know what is taking place is very wrong. This system of granting special financial benefits to one category of citizens, and the strong desire of those who have been entitled to preserve the status quo, has the effect of locking the majority of reserve residents into chronic poverty, drug addiction, suicide, and hopelessness.

Our current Federal government claims that its goal in expanding the number of eligible status Indians is to achieve reconciliation. However, it is increasing the divide that already exists between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

Maintaining a regime of separate laws for one class of citizens is, and has always been, a bad idea. Our politicians and courts have served us very poorly in creating and perpetuating this “crazy quilt” of a system with different classes of citizens, each with different rights.

The solution is simple and obvious; we must move toward a Canada with the same entitlements and the same responsibilities for everyone. The challenge is to find a solution that will fairly compensate Indigenous people for their inherited treaty rights, and enable Canada to become a truly modern country in which people are not separated by racial divisions.

It is time to change the “status” in status quo.

[i] http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/indian-status-5-things-you-need-to-know-1.2744870

[ii] http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/indian-act-legislation-change-course-1.4392291

[iii] http://www.metisnation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/PST-LLP-Summary-Daniels-v-Canada-SCC-April-19-2016.pdf

[iv] http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/métis-non-status-indian-ruling-could-cost-billions-1.1319948

[v] http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/lynn-gehl/checking-the-math-behind-carolyn-bennetts-2-million-new-indians_a_23247909/

[vi] https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/NewLookCanadianIndianPolicy.pdf

[vii] http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/aboriginal-population-statistics-canada-1.4371222

[viii] http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/decision-week-for-qalipu-band-1.3967117

[ix] https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/reserves-gripped-by-poverty-census-450362963.html

[x] See Harold R. Johnson’s book: “Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing My People (and Yours).

View the PDF version here: EF14StatusGiesbrecht_F2