Canada is, without question, a land of historic treaties, particularly in the West.

There were treaties between the Hudson’s Bay Company and Indigenous communities in Rupert’s Land for building trading posts and using waterways.

The Métis of the Red River Settlement and the Dakotas had peace and trade treaties.

Treaties between the Cree and Dene demarked territories and set protocols for travelling in shared areas.

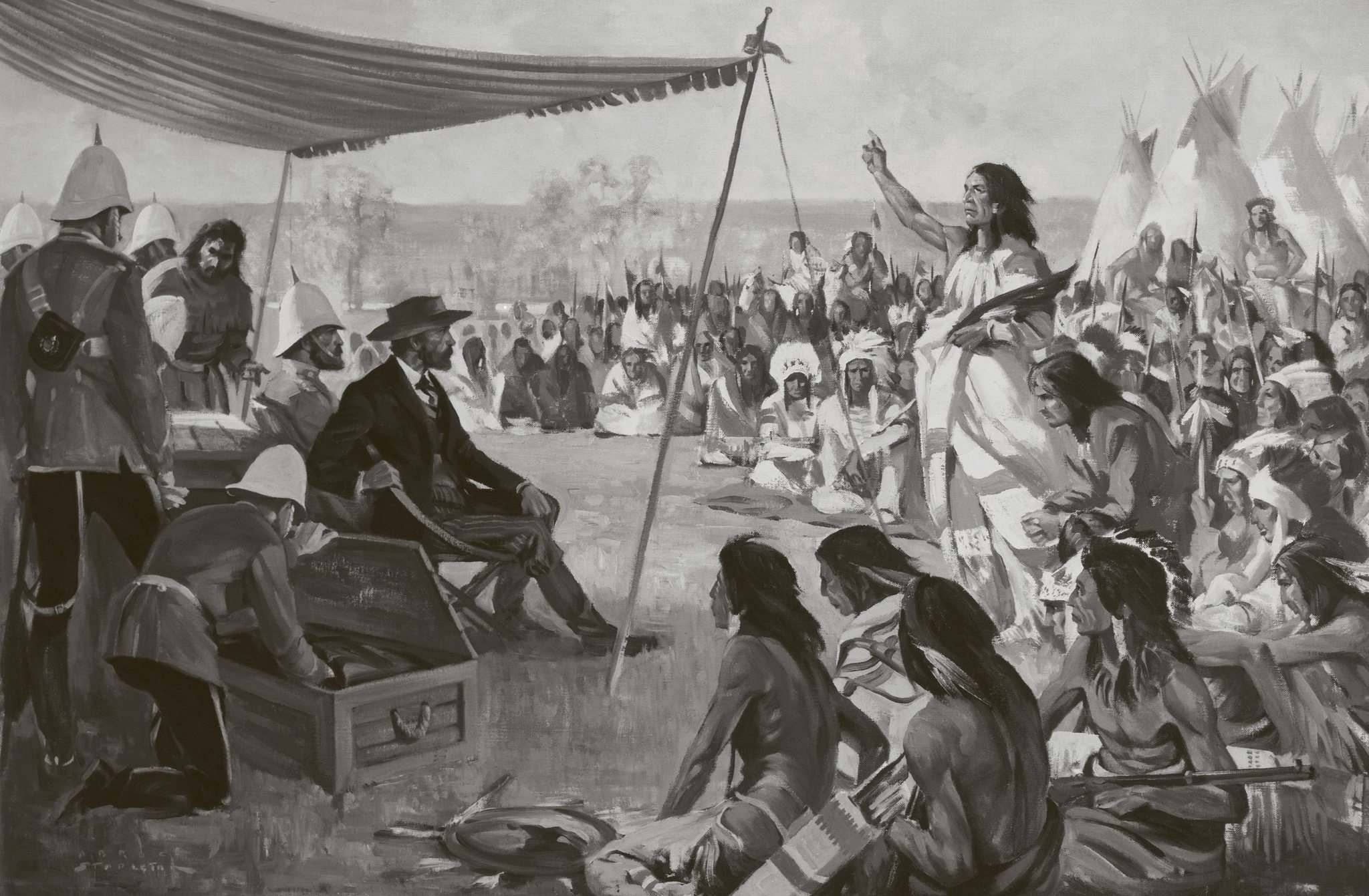

All of these and many more pre-dated the more familiar numbered treaties, stretching from Thunder Bay to the Rockies, signed from 1871 onward.

Author and historian Sheldon Krasowski’s deep dive into the negotiations of the numbered treaties (numbers 1-7) offers a direct challenge to the long-accepted “cultural misunderstanding” thesis.

Dating from the 1930s, researchers proposed that the cultural and linguistic differences between Euro-Canadian and Indigenous negotiators were so great that Indigenous people were unable to properly understand the meaning of the treaties they were signing.

In No Surrender: The Land Remains Indigenous, Krasowki turns this notion on its head. He argues, in great detail, that Indigenous negotiators knew very well what they were signing. With the exception of Treaty 3, it was Indigenous leaders who demanded treaties be signed to secure their peoples’ future before they would allow settlers and surveyors on their traditional lands.

Indigenous leaders knew they had a strong hand when numbered treaty negotiations began in 1869. The Anishinaabe west of Lake Superior were already charging right-of-way fees to settlers heading to the Prairies, and they knew that the Canadian government wanted to send troops through their territory to the Red River to put down the Riel Resistance. Negotiations in Fort Frances, Ont. finally broke down in 1871 over the Anishinaabe demands that were far more than the Crown negotiators could sell to Ottawa.

The Crown negotiators quickly moved on to Lower Fort Garry, under pressure from the federal government to close a deal with the Cree and Saulteaux. Ottawa wanted to make way for settlement in the new Manitoba province, and to clear the way west for a railroad, a condition for British Columbia joining the Confederation. And there was always concern about Americans casting covetous eyes upon the vast North-West.

Treaty 1 took three weeks of negotiations. In particular Henry Prince, the eldest son of Chief Peguis, questioned why the Indigenous people should have reserves. Did it not make more sense, he suggested, that the settlers be granted reserves, the same as when the Selkirk settlers were granted the use of the land along the Red and Assiniboine rivers under the Selkirk Treaty of 1817?

Krasowski states that land sharing was a crucial issue in Treaty 1 negotiations, which set the template for the numbered treaties that followed. It focused on three key points: reserved lands would be for the exclusive use of Indigenous people; the remaining lands would fall under joint Indigenous and Canadian jurisdiction; and farmlands would be set aside for settlers, with Indigenous people retaining the right to gather, hunt or fish on the rest of the land.

What was missing from this discussion was any mention of land surrender.

“The commissioner’s strategy of agreeing to share the land while avoiding discussion of the surrender clause originated with Treaty One but continued with the later numbered treaties,” states Krasowski. He adds that “avoiding the surrender clause during negotiations was a cornerstone of Canada’s negotiating strategy.”

The author arrived at this conclusion by “treaty bundling,” meaning he studied the seven treaties as a cohesive whole.

Along with the well-studied writings of the commissioners and others, Krasowski also incorporated diaries, letters and other contemporaneous materials of witnesses, some of which had been previously overlooked. He also included Indigenous oral histories, with careful attention to bias and context. Using this approach, he concludes that Indigenous lands were never surrendered.

It seems a contradiction to say that Indigenous negotiators knew what they were doing during negotiations, but then claim that they were deceived when it came to the land surrender clause.

It implies that trusted advisers and interpreters such as James McKay and Peter Erasmus were either in on the ploy, or somehow deceived as well. For all seven treaties. The author does not seem to have an answer for that.

No Surrender is a welcome addition to new research that helps reframe Indigenous issues. It is a hefty work at 368 pages, and does tend to be repetitious in places. However, it is a worthwhile read for those with a keen interest in understanding Canada’s numbered treaties.

(Appeared originally in the Winnipeg Free Press, March 9, 2019)