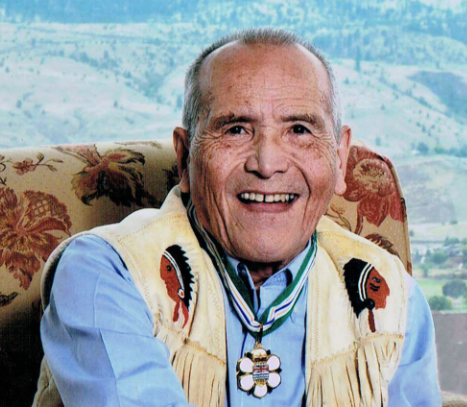

November 16 marked 88 years since the birth of Canada’s first “Status Indian” Member of Parliament and cabinet minister, Leonard Stephen (Len) Marchand. Elected, then re-elected twice, to the House of Commons, he served as a parliamentary secretary, minister and, later, member of the Senate. His first election in 1968 when he defeated high-powered Tory E. Davie Fulton to win the Kamloops-Cariboo seat for the Liberals came just eight short years after John Diefenbaker’s government granted status Indians the right to vote.

Born in 1933, Marchand’s life story, chronicled in his autobiography Breaking Trail, was one of accomplishment, the pursuit of happiness, and service to Canada.

Marchand was a former student at the now notorious Kamloops Indian Residential School (KIRS). Much of Breaking Trail, published in 2000, documents his experience at the school and reveals that he was never a mere “survivor” or would ever view himself as such.

Allegations these past months about unmarked graves at the KIRS have reminded me of the seventies when I was employed as a Hansard reporter in the House of Commons. One of the members of the House was MP and cabinet minister, Len Marchand. I fondly remember the soft-spoken, witty, sincere, humble and yet confident parliamentarian that he was.

Yes, I was impressed by Len Marchand’s performance as an MP, but I was not the only one. He was appointed parliamentary secretary to Indian Affairs Minister Jean Chretien and later as Minister of State for Small Business in Pierre Trudeau’s government. Later still, he became Minister of the Environment.

He was appointed to the Senate in 1984, serving there until 1998 when he was 64, retiring long before the rules required him to do so. He then involved himself with the Nicola Valley Indian Administration as its chief administrator. He died in 2016 at age 82, leaving behind a lifetime of achievement.

Marchand’s autobiography tells the story of his residential school experience and his life afterwards. It speaks modestly of his significant contributions to Indigenous Canadians, and all Canadians. Breaking Trail was published eight years before Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s 2008 apology for residential schools, before compensation for harm done, and before the anguish Canadians – Indigenous and otherwise – have endured since the apology.

Having previously attended elementary school on his reserve, at age 15 Marchand entered the Kamloops Indian Residential School (KIRS) for the 1949-50 school year. Despite his dislike of the food – “watery potatoes and over-boiled vegetables” – and, upon arriving, obliged to wash his hair in coal oil, he later described his time there as formative for his life’s successes. (“Kindly” Brother O’Brien told Marchand the coal oil was to “kill any lice.” The very clean-living Marchand noted the ordeal made him “a little upset.”)

He wrote: “I was already missing the pies and cakes my big sisters used to make. But there was plenty of milk and butter from the dairy herd and slabs of good bread. I soon learned that the thickness of your slice was a status symbol. A thicker crust meant you had a girlfriend who was a big wheel in the kitchen.” There is no mention of hunger, let alone starvation.

About conditions in the classroom, he wrote: “…the staff did put a definite priority on giving us an education. The classrooms were big, well-lit rooms, with desks as modern as any you could have found on the west side of Vancouver in 1949.”

“And the teachers were just as good.” Marchand went on to describe the commitment of the nuns to the students’ education, and added, “…and most of us responded.”

Perhaps the most notable observation Marchand made about his time at Kamloops school was that: “… another motivation took root in the back of my mind: that somehow, by getting educated, I would be able to do something to help my people. I don’t remember the first time that idea came to me, but it probably sprouted sometime during the year that I spent at Kamloops Indian Residential School.”

Marchand enjoyed playing sports at the school – baseball, basketball and hockey – admitting in his book that he was not very good at any of them, performing better in his classroom studies. Still, he took pleasure in the sporting achievements of his teammates and wrote proudly about the school’s Holstein cattle winning blue ribbons at the Armstrong Fair, and Sister Anne Mary’s “superb” choir “cleaning up” at the annual local choral festival.

In many ways, directly and indirectly, Marchand made it clear that his days at the KIRS were happy ones. Today, reports of happy times at any of the schools are met with angry demands for retraction and apology.

Story-telling about the Indian Residential Schools (IRS) by its former students has changed mightily in recent years. Twenty-one years ago, Marchand was not afraid to write, “I was never abused, and I never heard of anyone else who was mistreated at the Kamloops school.” He did not fear writing positively about the priests, nuns and brothers: “… they meant well by us, they genuinely cared about us, and they all did their duty by us as they saw fit.”

Those words are important, because having lived since 1933 in a region comprising several Indian reserves, having attended a reserve day school and the KIRS, and having risen to lofty federal positions of power, a member of parliament – especially an Indigenous one – gets to know all the leadership people in the region he represents, including mayors, chiefs, elders and knowledge keepers. Len Marchand was a very good member of parliament. Good MPs talk to people, listen to people, help people, exchange stories, learn about the “knowings” of the elders, knowledge keepers, former residential school students and their families.

Marchand was there. Marchand was well connected. Marchand never experienced, never witnessed, and never heard about the “horrors” we’re hearing about today.

This is an important observation: today, 72 years since Len Marchand attended the KIRS, chiefs, knowledge keepers and others are presenting sometimes detailed though second-hand stories about events that Len Marchand never heard a word about. Why today? Why not then?

Williams Lake, B.C., Mayor Walt Cobb was recently condemned for reposting an online suggestion that there might be more than one side to the IRS story. He was forced to apologize and came very close to losing his job. He must now be re-educated. Len Marchand’s story included his own experience at the KIRS and covered many of his years in public life. We can only wonder, if he were still alive, what he would say about the IRS revelations.

Len Marchand’s education did not end at the KIRS. He was a lover of learning and was consumed with helping his people. He earned a master’s degree in forestry and secured employment as an agronomist prior to beginning his work in Ottawa, the nation’s capital. His work with parliamentarians in Ottawa led to his being approached to run for office in Kamloops-Cariboo, which he did, in the process making history.

Quite unabashedly, Len Marchand wrote of his love for and pride in Canada. Is anyone doing that these days? Yes, Marchand identified himself as a Skilwh of the Okanagan Nation, preferring that appellation to that of Aboriginal, Indian, native, or First Nations, an appellation he called “pretentious, politically loaded” But first and foremost, Len Marchand identified as a proud Canadian.

James C. McCrae, former Canadian citizenship judge, MLA and attorney general for Manitoba.