Homes in Delta, B.C. Photo by Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press files

When it comes to safeguarding our property rights, we shouldn’t leave it to the whims of politicians and policymakers. Rights that are subject to a politician’s whims might as well not be rights at all.

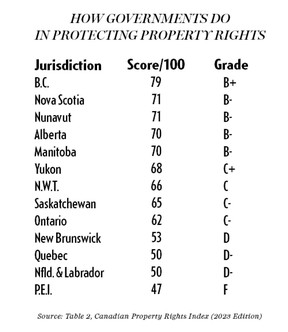

The solution is a vigilant public that insists government address areas of weakness. To my mind, that is one of the central takeaways from the Canadian Property Rights Index, which I oversee for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. First launched in 2013, the index provides disturbing evidence of the precariousness of our property rights, thanks to ongoing legislative efforts to diminish them. In our latest ranking, for 2023, the best mark any jurisdiction received was a B+, which went to British Columbia. Prince Edward Island ranked lowest with an F. That no jurisdiction scored higher than a B+ is a serious concern. It suggests that all provinces and territories must work harder to create stronger procedural safeguards for property owners.

The index examines seven specific indicators: land title, expropriation, regulatory takings, civil forfeiture, protection for property rights when enforcing either heritage or endangered species legislation, and municipal power of entry, which refers to the power of municipal officials to enter onto private land in executing bylaw enforcement.

All 10 provinces and three territories are assessed on each of these indicators. The higher a jurisdiction’s score on an indicator, the more it safeguards property rights. All seven indicators get the same weight.

A key insight from the index is the uneven enforcement of property rights both across the country but even within a province. For example, despite ranking highest overall, British Columbia only scores 67 per cent in regulatory takings — which occur when regulations enacted by the government prevent a property owner from making any beneficial use of their property. B.C.’s Agricultural Land Reserve, which restricts land rights and removes potentially valuable housing land from development, is also a blemish on the province’s record. On the other hand, B.C. has good procedural safeguards protecting property rights in other areas, such as expropriation or enforcement of endangered species legislation.

Some Atlantic provinces have lower scores partly because they have an older title registration system that is less reliable than the newer Torrens systems, which maintain a central registry of lands that is more accurate, less costly and is insured against errors. PEI’s lack of a Torrens-style land title system and its weak protections in areas like expropriation, regulatory takings, endangered species legislation and heritage properties contribute to its low ranking. However, a plus for PEI is that it lacks civil forfeiture laws.

Although Quebec’s civil law system provides some relief from regulatory takings, the province performed poorly overall (with a mark of 50 per cent) because of lower scores in areas like land title, expropriation, endangered species legislation and municipal power of entry.

Joseph Quesnel is a senior research associate with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. He is the author of the newly revised Canadian Property Rights Index 2023.

Related Items:

Read commentary by Joseph Quesnel; To Finally Kill Colonialism, Give Property Rights to First Nations Individuals,

Read Supreme Court’s Annapolis Ruling A Win For Property Owners by Joseph Quesnel.