In a recent National Post commentary titled The reality of Indian Residential Schools was neglect and abuse, archaeologist Paul Racher criticizes those who dismiss the term “genocide” in relation to the Indian Residential Schools system as an exaggeration. However, the arguments he presents to support his claim only serve to demonstrate that the abuses he mentions fall light-years short of proving his point.

Regrettably, it appears that Racher may not have read all of the Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) report’s 3,400 pages. If he did, he would notice that every point he makes is contradicted in the report.

Racher alludes to a higher mortality rate from diseases like tuberculosis among Indigenous Residential School (IRS) children when compared to their white counterparts. This statistic should not surprise anyone familiar with the inadequate health conditions present in the reserves from which these students came. This was documented in the TRC report.

These children often brought illnesses such as TB, diphtheria, influenza, and other communicable diseases with them. Additionally, when considering rates of illness, it is essential to compare the IRS not with the general population but with similar confined environments such as industrial schools, private boarding schools, jails, and the communities from which these children originated.

Racher should also acknowledge that the majority of IRS deaths occurred before 1945, when there were few cures for epidemic diseases. In the era of antibiotics and polio vaccines, the mortality rates at residential schools were closely matched by those of the broader Canadian population.

Racher also states, “Indigenous children were routinely snatched from their parents”. After 1920, native children were required to attend school. So was every other Canadian child. For families living in remote communities or working on traplines, residential schools were often the only educational option available. This was an option that only about 30 percent of indigenous families opted for over the long history of the IRS. Moreover, parents had to apply for their children to attend.

According to one source interviewed by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), “Who came to residential schools? The elite. The councillor’s children, his family’s children, the Chief’s children … They were wonderful kids. They were smart kids. So they were the elite … because their parents knew that someday their kids would need to be educated.” Many of the children who attended residential schools were also there because their homes or reserves were unsafe due to physical, sexual, or substance abuse. The IRS system served as a refuge for many vulnerable young people.

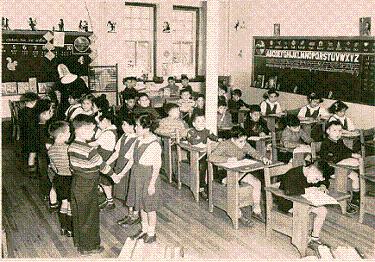

If some, like RoseAnne Archibald, the Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, claim that the IRS system was a deliberate attempt to exterminate native children, then what are we to make of the efforts made to nurture and develop the students? What about the positive comments made by students about caring teachers? The trips to Disneyland and hockey tours of Europe? The involvement in cadet, Boy Scout, Sea Scout, and Girl Guide groups, and trips to the World Jamboree in the U.S.? The lessons in native culture and arts? Sports leagues, dance tours, and glee clubs? All of these activities are documented in the TRC Final Report but are ignored by Ms. Archibald and Mr. Racher.

When it comes to the claim that thousands of residential school children were secretly murdered and buried surreptitiously, Racher is on even shakier ground.

He has stated elsewhere in the case of the Kamloops school that he was “devastated by news of the discovery of child burials”, but he should know – better than most, as a professional archaeologist – that subsoil anomalies detected by ground-penetrating radar do not necessarily indicate the presence of human remains. He defends the lack of evidence at Kamloops to an Indigenous cultural dislike of exhumation, yet Canadians of all cultures view exhumation with distaste.

We are not a nation of grave robbers, but in the event of a reported crime, particularly one of such allegedly horrible proportions, we overcome our revulsion and require that the victims’ bodies be recovered and examined. If there are children in the Kamloops orchard buried, as is claimed, by their fellow students as young as six using their bare hands, then monstrous deeds have been done and justice is required and closure brought to their families.

If there are not, which can only be determined through excavation, then the reconciliation we all desire becomes easier. Until such time, claims of genocide are overblown and should be avoided. These facts cited are from the TRC report, which, sadly, few Canadians have bothered to read. Facts do matter, especially if we are to have healthy discussions on difficult topics in our society, let alone achieve reconciliation so we can build a better Canada for everyone.

Gerry Bowler is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. Watch Gerry Bowler on Leaders on the Frontier here.