Most people have heroes, people in history or people still living, people who inspire, evoke strong feelings of admiration, respect, love.

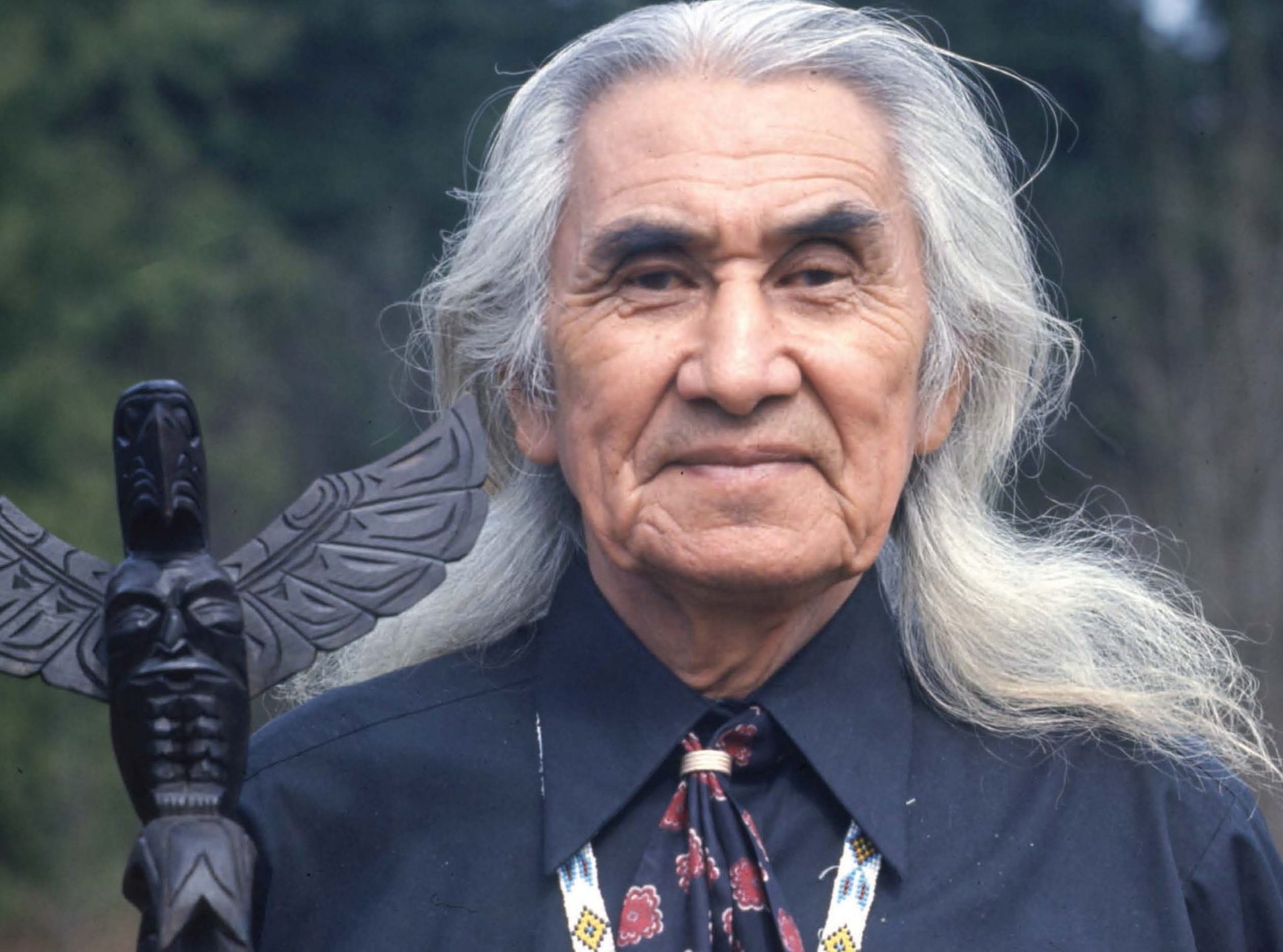

High on my list of heroes is Geswanouth Slahoot, aka Chief Dan George. The more I learn about him, the higher his name climbs.

A little boy on his Tsleil-Waututh Nation reserve, student, longshoreman, lumberman, school bus driver, musician, Tsleil-Waututh Nation chief (1951-63), actor, lecturer, carver, poet, activist, environmentalist. There might not have been time for much more to occupy his life but, as my study reveals, “family man” was probably at the top of his personal list of accomplishments (six children, 36 grandchildren).

George’s father, Chief George Slah-holt, had also been chief of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation (Burrard Reserve – Coast Salish). Following in has father’s footsteps, Dan George’s son Leonard George, also served as chief of the band, between 1989 and 2001.

Dan George and at least five of his six children – including son Leonard – attended school at St. Paul’s (Squamish) Indian Residential School in North Vancouver, B.C. Given his father’s wish that Dan learn the English language, it is a fair assumption that some – or all – of his eleven siblings also attended that school.

Dan entered St. Paul’s shortly after his fifth birthday, in 1904, 16 years prior to the 1920 Indian Act amendment mandating compulsory school attendance for First Nations children. He was not forced to attend, except in the sense that his father sent him there. But it was at the school where he was assigned the surname George, which remains the anglicized family name today.

Dan George attended St. Paul’s for eleven years, visiting family twice monthly on the reserve a few miles away. He was not allowed to attend past the age of 16. Through an arranged marriage at the age of 18 or 19, he wedded 16-year-old Amy Jack, with whom he lived for more than 50 years, until her death in 1971. Thus began the life of the family man.

Of all his many outstanding experiences and achievements, Chief George cited as “the happiest times of his life” the times he spent with his family, in the 1940s. He had formed “Dan George and His Indian Entertainers”, traveling British Columbia, performing traditional dances and ceremonies, and wearing traditional clothing. He later formed the “Children of Takaya (wolf) Dance Group”.

The above is to say little about Dan George’s many significant accomplishments and awards, well known to Canadians, including an Oscar nomination (Little Big Man,1970), Order of Canada (1971) and others.

It would be hard for anyone not to have complete admiration for a person of the stature of Chief Dan George. I admire him for all his achievements, but perhaps the most gratifying for him was that he was able to bridge the chasm – still not bridged by so many others – between his Indigenous roots and the world he had been brought into. Loved by his own people, loved by everyone else, he mastered life in the modern world while truly living and savouring his original culture, and sharing it with all around. This should be his legacy; this should be the example for others still struggling to find their way.

Given that he received only eleven years of formal education at a residential school in the very early years of the last century, his life’s work was even more remarkable. He clearly learned something immensely important at that school.

If they were still with us, Dan George and his wife Amy would surely be proud of the results of the legacy they left their family, many members of which have thrived. The George family includes writers, an academic, actors, politicians, activists, a playwright, a poet, a teacher.

His role in the film Little Big Man brought the name of Chief Dan George to kitchen tables across Canada and well beyond. But what he really did was personify what everyone claims to want for themselves, and for our country. In his centennial 1967 “Lament for Confederation” he said:

“I must forget what’s past and gone … Oh God in heaven! Give me back the courage of the olden chiefs … Oh God! Like the thunderbird of old I shall rise again out of the sea; I shall grab the instruments of the white man’s success – his education, his skills, and with these new tools I shall build my race into the proudest segment of your society … So shall we shatter the barriers of our isolation. So shall the next hundred years be the greatest in the proud history of our tribes and nations.”

That was 56 years ago. Dan George clearly recognized that reconciliation is a two-way street. But crippling isolation continues to paralyze our country. It grows as Canadians squabble over what to believe about our past and how to move forward. Why can’t we look at the life of Chief Dan George, memorize his words, and turn the page? Dan had the answer:

“The only thing that can truly help us is genuine love. You must truly love us, be patient with us and share with us. And we must love you with a genuine love that forgives and forgets … a love that forgives the terrible sufferings your culture brought ours when it swept over us like a wave crashing along a beach … with a love that forgets and lifts up its head and sees in your eyes an answering look of trust and understanding.”

Let’s be like Dan.

James C. McCrae, is a former attorney general of Manitoba and Canadian citizenship judge