Yuri Bezmenov has been dead for decades, but his words have renewed attention. The former Soviet journalist and KGB operative defected to Canada in 1970 and adopted the name Tomas Schuman. Although he died in 1993, his writings, lectures and interviews have found new life in the internet era. They even formed the trailer1 for the Call of Duty Black Ops Cold War video game.2 There’s a good reason for his renewed fame. Bezmenov speaks authoritatively about the horrors and methods of a totalitarian Marxist state.

Bezmenov was born in 1939 near Moscow, the son of a high ranking Soviet Army officer who inspected Soviet troops outside of Russia. At the age of 17, the younger Bezmenov entered the Institute of Oriental Languages at Moscow State University. The institution was controlled by the KGB and the Communist Central Committee, and many graduates became diplomats, foreign journalists, or spies. His compulsory military training taught him how to play strategic war games and even interrogate prisoners of war.3

As a young man, Bezmenov volunteered to bring in the grain harvest in Afghanistan.4 In his book “No Novosti is Good News,” he recalls how he had been told in childhood that “overproduction” among “free market” capitalists was “so badly organised and so greedy, that they prefer to burn wheat and pour milk into rivers rather than give it to the poor masses.”5 Bezmenov eventually realized this caricature would still have been better than his everyday life.

In my Motherland there is no danger of overproduction, that I can witness after 30 years of socialist life. Shortages, but only as temporary complications of rapid socialist growth [he says, sarcastically]. We may sometimes be short of potatoes, bread, matches, shoelaces, shoes, coal, kerosene, sheet iron, soap, strawberry jam, ballpens, living space, corn, wheat, meat [and many other things]. But not for a single second in the history of socialism have we been short of propaganda. This semi-fluid we produce in abundance for ourselves and for our foreign brothers.6

How hard is truth to find under a Marxist regime? Its journalists can’t even find it. Bezmenov needed his short-wave radio set to find out the real news, even when he was employed with the state media, Novosti.

I spend hours by the set, tuning to the Voice of America, BBC and Deutsche Welle for news from abroad: Radio Luxemburg and Radio Teheran, for music: All India Radio, for nostalgia. But the most exciting for me is Radio Svoboda (or Radio Free Europe), the station that informs me about happenings in my own country. It is an irony: I work for a news agency.

How meaningful are lives under a Marxist dictatorship? In a 1984 interview with author G. Edward Griffin, Bezmenov said people were worthless. “It’s a state capitalism, where an individual has absolutely no rights, no value; his life is nothing; it’s just like an insect. He is disposable.”

Bezmenov said few citizens, if any, conscientiously supported the system because “it hurts, it kills.” Even relatively affluent journalists like Bezmenov hated Soviet oppression because “they are unfree to think, they’re in constant fear, duplicity, split personality. And this is the greatest tragedy for our nation.”

Or maybe not. Bezmenov seemed to describe a worse tragedy when he said, “We sure know from various sources that at each particular time there are close to 25 to 30 million of Soviet citizens who are virtually kept as slaves in a forced labour camp system. The size of the population of a country like Canada is serving terms as prisoners.”

Whatever the sins of western colonialism were, or arguably are, they are unworthy of comparison to that of a conniving and brutal Marxist regime. Over time Bezmenov realized just how bad the system he was brainwashed into believing in actually was.

My first assignment was to India as a translator with the Soviet Aid Group, building refinery complexes in Bihar State and Gujarat State. At that time I was still naively, idealistically believing that what I was doing contributed to the understanding and cooperation between the nations. . . . at that time I was still hoping that well, maybe it’s not that bad, could be worse, and things may go for better. And I even tried to implement the beautiful Marxist motto, ‘Proletarians of all countries unite!’

Bezmenov fell in love with India and even wanted to marry an Indian girl. But the Union of Soviet Socialistic Republics made the bedrooms of the nation its business as well, as Bezmenov explains.

In the span of my career, I married three times. Most of these marriages were marriages of convenience on advice from the Department of Personnel. This was normal practice in the USSR. When a Soviet citizen is assigned to a foreign job, he has to be married, either to keep family in USSR as hostages, or, if it’s a convenience marriage like mine, so that the husband and wife are virtually informers on each other, to prevent defection or contamination by decadent imperialist or capitalist ideas. In my case, I hated that girl so much that the moment I landed in Moscow we were divorced.7

In 1965, Bezmenov started to work for Soviet-controlled media outlet RIA Novosti in their classified department of political publications. Bezmenov wrote, edited and planted propaganda materials in foreign media. He also hosted Novosti guests when they came to tour the Soviet Union or attend international conferences. Later, Bezmenov was forced to be a KGB informant, while continuing his position with Novosti.

In 1969, Bezmenov was assigned to India as a Soviet press officer and public relations agent in New Delhi. That year the Central Committee launched its newly-formed “Research and Counter-Propaganda Group,” which would operate in all Soviet embassies worldwide. As part of the group, Bezmenov gathered intelligence from Indian informers and agents on influential or politically significant citizens.8

As he would later tell author G. Edward Griffin in 1984, Bezmenov developed a “moral indignation, moral protest rebellion against the inhuman methods of the Soviet system.”9 As a student he’d objected to “oppression of my own dissidents and intellectuals.” Things came to a breaking point while working at the embassy in India.10

To my horror, I discovered that we are millions [of] times more oppressive than any colonial or imperialist power in the history of mankind, that my country brings to India not freedom, progress, and friendship between the nations, but racism, exploitation, and slavery, and again, of course, economical inefficiency. . . I decided to defect and to entirely disassociate myself from the brutal regime.11

Bezmenov had hosted visiting journalists and other intellectuals on their visits to Soviet Russia. He also developed such relationships while stationed in New Delhi, just as his comrades did in Hanoi, Vietnam. But Bezmenov made a chilling discovery. “To my horror I discovered that in the files were people who were doomed to execution. There were names of pro-Soviet journalists with whom I was personally friendly.”12

The foreign journalists were merely pawns to be sacrificed.

So most of the Indians who were cooperating with the Soviets, especially with our Department of Information of the USSR embassy, were listed for execution. And when I discovered that fact, of course I was sick: I was mentally and physically sick. I thought that I [was] going to explode one day during the briefing of the Ambassador’s office; I would stand up and say something [like], “We are basically a bunch of murderers. That’s what we are. It has nothing to do with ‘friendship and understanding between the nation[s]’ and blah-blah-blah. ‘We are murderers! We behave as [a] bunch of thugs in a country which is hospitable to us, a country with ancient traditions.’”13

Bezmenov said after a military revolution, the KGB would have their former allies “lined up against the wall and shot,” since the original Marxists would never share power with the ideological leftists. The reason? “Because [laughs] they know too much. Simply, because you see, the useful idiots, the leftists who are idealistically believing in the beauty of [the] Soviet socialist or Communist or whatever system, when they get disillusioned, they become the worst enemies.”14

The Soviet system was so debilitating, dehumanizing, and unsustainable that Bezmenov predicted its demise in 1984, a few short years before it actually took place. “There is a great possibility that the system will sooner or later be destroyed from within. There are self-destructive mechanisms built into any socialist or communist or fascist system. There is a lack of feedback because the system does not rely upon loyalty of population.”15

When Bezmenov discovered Soviet plans to cause a revolution in neighbouring East Pakistan, now called Bangladesh, he decided to defect. He began to wear a disguise and hang out with American leftist hippies in his off-hours. Bezmenov said these students who were smoking drugs and “pretending to study” were the “laughingstock” of India. Yet, when a group of them made a tour to Athens in 1970, he joined them for his great escape. The Central Intelligence Agency interrogated him for months and finally arranged his defection to Canada under the name Tomas Schumann.16

Bezmenov told Griffin in 1984 he was already surprised how far Marxist indoctrination had advanced during his 14 years in the West. Leftist intellectuals had taken many places of influence in Canada and the United States, a testament to the success of the Marxist subversion and propaganda he wanted to expose.17

In 1984, Griffin told Bezmenov, “I think you’re trying to tell us something… to this country.”18

“Oh yes,” Bezmenov replied. “I am trying to tell you that it has to be stopped, unless you want to end up in [a] gulag system, and enjoy all the advantages of socialist equality, working for free, catching fleas on your body, sleeping on planks of plywood, in Alaska this time, I guess. That’s where Americans will belong unless they will wake up, of course, and force their government to stop aiding Soviet fascism.”19

Bezmenov died in 1993, long enough to see the Soviet Union fall apart. Even so, our times have witnessed more Marxist propaganda than ever. Millenials and post-millenials have no memories of the Cold War, but many have been taught Marxist critical theory and political correctness. Bezmenov is dead but his warnings live on. Unfortunately, they may be more relevant than ever.

Lee Harding is a research associate with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

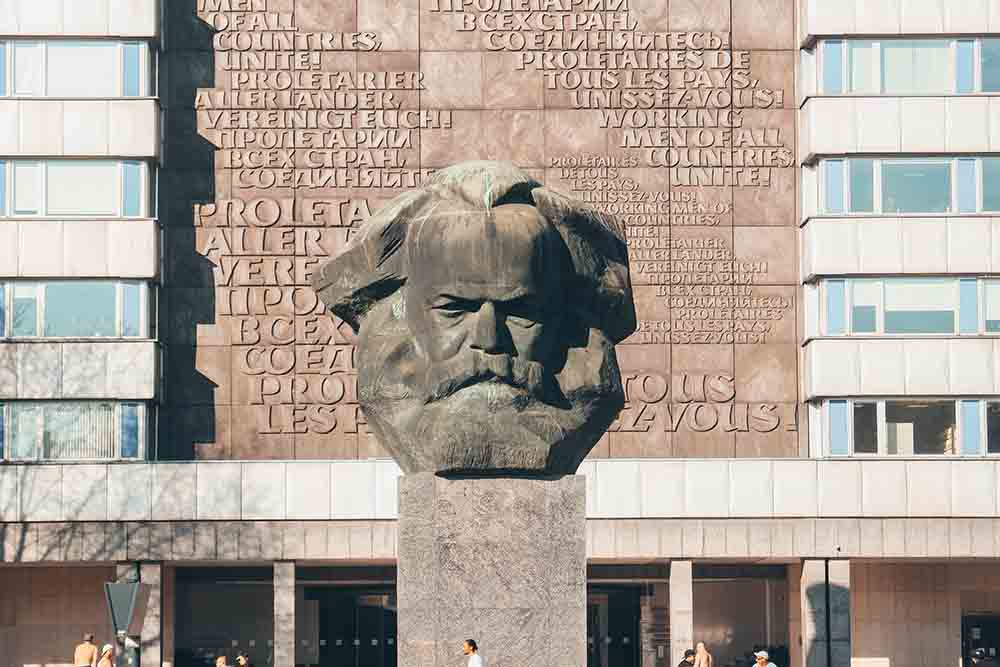

Photo by Maximilian Scheffler on Unsplash

[show_more more=”SeeEndnotes” less=”Close Endnotes”]

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zsBRGCabaog

- https://ca.news.yahoo.com/call-duty-cold-war-announced-172718495.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jFfrWKHB1Gc

- Ibid.

- https://archive.org/stream/BezmenovNoNovostiIsGoodNews/NoNovostiIsGoodNews_djvu.txt, p. 32.

- Ibid.

- Bezmenov’s comments to Griffin can also be found in print form at http://uselessdissident.blogspot.com/2008/11/interview-with-yuri-bezmenov-part-two.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20101101152925/http://www.scribd.com/doc/26265794/World-Thought-Police-Yuri-Bezmenov

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jFfrWKHB1Gc

- His quotes, here and as follows, continue verbatim, despite some slight grammatical errors including missing definite articles.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jFfrWKHB1Gc

- http://uselessdissident.blogspot.com/2008/11/interview-with-yuri-bezmenov-part-three.html

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

[/show_more]