You have heard of preparations for blizzards, tornadoes and hurricanes, but have you ever heard of preparing for a solar storm? A severe coronal mass ejection (CME) could make life in the 21st century look like the worst of the 19th, causing a disruption few will be ready to face. Regardless, governments, power companies and citizens don’t have to be caught flat-footed.

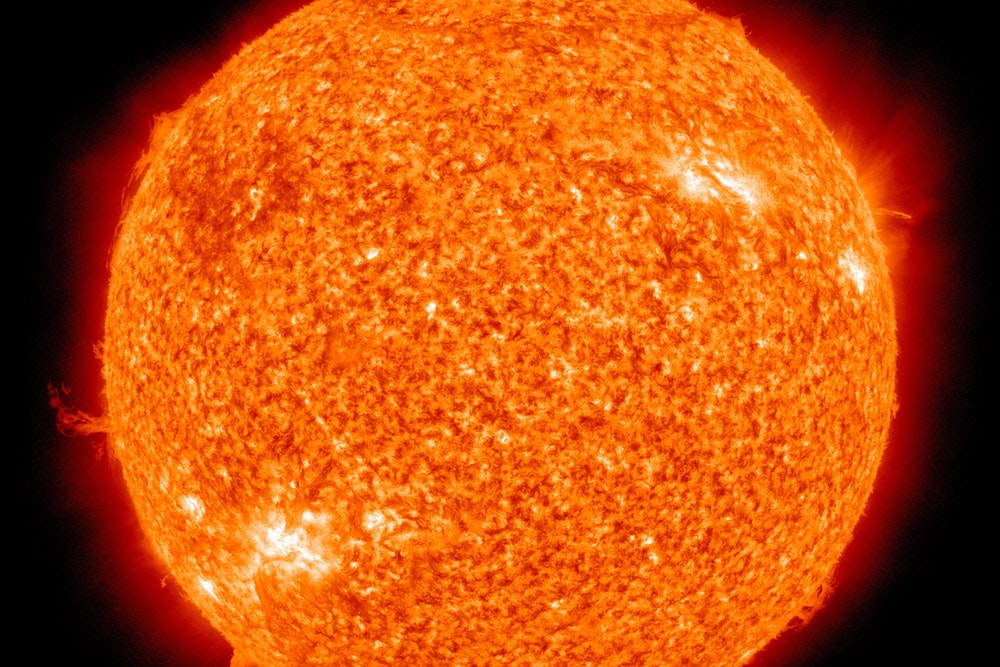

In a CME, part of the sun breaks loose due to fluctuations in the star’s magnetic fields. The hot plasma and charged particles in a CME can weigh up to 220 billion pounds and travel at speeds of 11 million kilometres per hour. If they reach the Earth, electrical systems can suffer severely, damaging the grid so badly that blackouts ensue. The Earth’s magnetic field tends to draw the electrical charges from a CME to the north and south poles. This means Canadians could face the worst effects as occurred in Quebec almost 33 years ago.

On March 13, 1989 a geomagnetic storm caused a nine-hour outage of Hydro-Québec’s electricity transmission system. In about 90 seconds, the electrical grid went from normal operations to a province-wide blackout that took nine hours to rectify. The shock to the system was also felt in various parts of North America and Europe. In New Jersey, for example, not only was the insulation on one 220-tonne transformer burned out, but the copper was melted—a feat only possible at temperatures over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

The storm caused power surges at electrical grids for 30 hours, but could have been even worse. In a YouTube video on the 1989 event, engineer John Kappenman of Storm Analysis Consultants said, “It’s always been our good fortune when we’ve had blackouts to be able to restore them within a couple of days. If we have a big blackout caused by a space weather event, a much more intense space weather event, we may find that it is difficult if not impossible to restore and may take weeks, months, perhaps years.”

Consider the Carrington Event of September 1–2, 1859, caused by a CME three times more powerful than the one in 1989. British astronomer Richard Carrington saw a “white light flare” in the solar photosphere, but soon much of the world faced a spectacle impossible to miss. Auroral activity was so widespread the northern lights were seen in Colombia and Australia. In the northeastern United States, people could read the newspaper by the auroras alone. Telegraph systems all over Europe and North America failed. Some telegraphs caught fire and some operators got electric shocks. So much electricity was circulating that some telegraphs could still give and receive messages even when disconnected from their normal power supplies.

In 2013, Lloyd’s of London and Atmospheric and Environmental Research (AER) in the United States estimated that if a similar solar storm to the Carrington Event occurred again, it would cause US$0.6-2.6 trillion damage to the U.S., equal to 3.6 per cent to 15.5 per cent GDP. But storms could be far worse. Signatures of carbon-14 levels in tree rings and beryllium-10 in ice cores suggest that an event in 775 A.D. showed 20 times the normal variation of solar activity and 10 or more times that of the Carrington Event.

A recent Global News report brought attention to the potential threat. Robyn Fiori, a research scientist at the Canadian Hazards Information Service, explained that we are approaching the high point of the 11-year solar cycle and large CMEs can occur. Satellites and ground-based instruments constantly monitor the sun’s activity and should provide a one- to five-day warning of such an event. A temporary shutdown of the electrical grid could mitigate risks of its permanent damage, though space satellites and fibre optic cables carrying internet connections could also be affected.

Electrical companies have made progress at securing the grid to withstand a one-in-100-years solar event, but that project is incomplete, to say the least. Any government representing the interests of its people would lean on power companies to enact the sorts of safeguards Hydro-Québec has put in place since the 1989 scare.

The Serenity Prayer says, “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.” We can’t do much to change the government, the power company, the sun or the weather, but we can prepare for the worst. A sensible response to global warming and climate change would be no different, but that would deserve a separate article.

The most basic form of personal preparation would be to have an alternative heating source and stores of emergency food and water. They would have proved handy to many residents in Ontario and Quebec when ice storms left them without power in January 1998. CME or not, it is always good to be ready. A once-in-150-year event might just come upon us.

Lee Harding is a research associate for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Photo by Pixaby on www.pexels.com